Protecting the Quiet Sky: How We Can Curb Unintended Satellite Radio Emissions

Why amateur radio operators, satellite internet users, and the scientific community must work together to reduce unintended radio emissions from low-Earth orbit satellites.

When I Tried Explaining This to My Kids

I tried explaining the LOFAR study 1 to my kids while they were watching television one evening, and I think the analogy actually works—though they were less than thrilled about my nerdy interruption of their Disney movie. Imagine I'm the satellite, standing right in front of the TV while I'm talking to you reading this article. My voice and my body are blocking their ability to see and hear their favorite Disney movie—that's essentially what satellites are doing to radio astronomy. The astronomers are trying to watch the universe's show, and the satellites are standing in the way, unintentionally but effectively blocking the view.

Now imagine there are thousands of me, all standing in front of that TV at once, each one adding their own voice and shadow to the problem. Their faces practically melted with shock and horror at the thought of thousands of me blocking their movie, and they said with complete seriousness and more than a little annoyance at my nerdy explanation, "I will never get to see the movie if that happened."

That's exactly the problem radio astronomers are facing—not with Disney movies, but with signals from distant galaxies, pulsars, and the cosmic microwave background that tell us about the universe's history and structure. The satellites aren't malicious, but they're still blocking the view, and the scale of the problem matters just as much as my kids understood it would, even if they were more concerned about getting back to their show than about my article.

The Regulatory Disconnect That Caught My Attention

As someone familiar with FCC Part 97 8 regulations, I've spent years learning how the Commission teaches amateur radio operators about spurious emissions, clean transmissions, and keeping our signals within authorized bands. We're required to reduce spurious emissions "to the greatest extent practicable," and we take that seriously because interference is a real problem that affects everyone. Yet here were satellites—thousands of them—emitting unintended radiation between 110–188 MHz, right through protected radio astronomy bands, and the regulatory response seemed... different. The contrast was stark enough that I had to dig deeper into what's happening, why it matters, and what we can actually do about it.

The issue isn't that satellite operators are breaking rules—they're largely operating within their allocated frequencies for intentional transmissions. The problem is that unintended emissions from onboard electronics, power systems, and interconnects are leaking into frequencies reserved for radio astronomy, and those emissions are raising the noise floor in ways that make it harder to detect faint cosmic signals. A single satellite might only add a whisper of interference, but when you multiply that by thousands of satellites in a constellation, and then multiply that by multiple constellations, the cumulative effect becomes significant. Radio astronomers are trying to listen to whispers from the universe while a growing fleet of satellites starts talking in the same room, and unlike the intentional signals we can coordinate around, these unintended emissions are harder to predict and mitigate. Understanding this problem requires looking at how radio astronomy protection actually works, what constraints satellite operators face, and how we can build cooperation frameworks that actually move the needle. The good news is that this isn't an unsolvable problem—it's an engineering challenge that needs better coordination, clearer standards, and more awareness from everyone who benefits from both satellite connectivity and scientific discovery.

How Radio Astronomy Bands Are Protected Globally

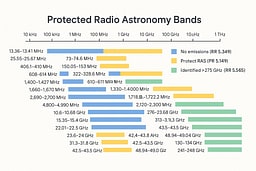

Radio astronomy operates at sensitivity levels that most engineers never encounter in commercial systems. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Radio Regulations 5 designate specific frequency bands as protected for the Radio Astronomy Service, meaning other services must avoid interfering with these frequencies to the greatest extent possible. These protections aren't arbitrary—they're tied to specific scientific observations that can only happen at particular frequencies. The 150–153 MHz range, for example, is where astronomers observe the 21-centimeter line from neutral hydrogen, which tells us about galaxy formation, large-scale cosmic structures, and conditions in the early universe. Other protected bands cover observations of hydroxyl masers, pulsars, and the cosmic microwave background, each requiring extreme sensitivity to detect signals that are often millions of times weaker than typical communication signals.

The ITU establishes these protections through a complex international coordination process that involves national regulatory bodies, scientific organizations, and industry representatives. ITU-R Recommendation RA.769 6 quantifies the protection criteria for radio astronomy, defining interference thresholds that are far more stringent than what commercial systems typically need to meet. These thresholds account for the fact that radio telescopes are designed to detect signals that might be only slightly above the thermal noise floor of the universe itself. The recommendation also establishes coordination zones around major radio observatories, where additional restrictions apply to prevent local interference from terrestrial sources. Sites like the Square Kilometer Array (SKA) 11 in Australia and South Africa, the Very Large Array (VLA) 14 in New Mexico, and the Green Bank Observatory 12 in West Virginia operate under these protections, with surrounding areas designated as radio quiet zones where even consumer electronics and power lines are carefully managed to minimize interference.

What "protected" means in practice depends on the specific ITU allocation and the regulatory framework in each country. In the United States, the FCC coordinates with the National Science Foundation and observatories to manage spectrum use near radio astronomy facilities, but the protections primarily apply to intentional transmissions within allocated bands. Unintended emissions—spurious and out-of-band radiation that leaks from electronic systems—fall under different regulatory categories, and the standards for satellite constellations operating in low-Earth orbit are still evolving to account for the scale and density of modern deployments. The IAU Centre for the Protection of Dark & Quiet Skies 3 works to coordinate between astronomers, satellite operators, and regulators to develop better mitigation strategies, but the regulatory framework itself needs updates to address the reality of constellation-scale operations. This gap between intentional transmission protections and unintended emission management is where the current problem lives, and it's why cooperation between all stakeholders becomes essential rather than optional.

Understanding Unintended Emissions: The Technical Reality

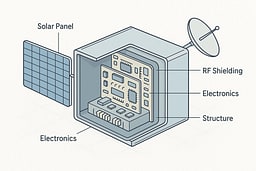

The LOFAR study detected unintended electromagnetic radiation from Starlink satellites between 110–188 MHz, frequencies that overlap with protected radio astronomy bands. These emissions aren't part of the satellites' intentional communication signals—they're byproducts of onboard electronics, switching power supplies, digital clock signals, and the interconnects between components. Every electronic system generates some level of unintended radiation, and satellite designers face the same fundamental physics that every RF engineer deals with: fast digital signals create harmonics, switching power supplies generate broadband noise, and any conductor can act as an antenna if it's not properly shielded or filtered. The difference is scale and location—when you have thousands of satellites in low-Earth orbit, each one contributes to a cumulative noise floor that affects ground-based radio telescopes trying to observe the faintest signals from deep space.

The technical distinction between spurious emissions and out-of-band emissions matters here, even though both can cause interference. Spurious emissions are unwanted signals at frequencies that are not part of the intended transmission, often harmonics or intermodulation products that result from nonlinearities in amplifiers or mixers. Out-of-band emissions are signals that fall just outside the authorized bandwidth but are still related to the intentional transmission. Both types are regulated under ITU-R Recommendation SM.1541 7, which establishes measurement procedures and limits, but the limits are designed for typical communication scenarios rather than the extreme sensitivity requirements of radio astronomy. A satellite might be fully compliant with ITU spurious emission limits and still generate enough unintended radiation to interfere with a radio telescope operating in a protected band, because those limits weren't written with radio astronomy's sensitivity requirements in mind.

Constellation scale amplifies the problem in ways that single-satellite analysis doesn't capture. A single Starlink satellite passing through a telescope's field of view might create a brief spike of interference that can be flagged and filtered out during data processing. But when you have thousands of satellites, the probability of multiple satellites being visible simultaneously increases dramatically, and the interference becomes more continuous rather than occasional. The LOFAR observations showed that in some datasets, up to 30% of images contained interference from Starlink satellites, which means astronomers are spending significant time and computational resources identifying and removing contaminated data rather than analyzing clean observations. This isn't just an inconvenience—it reduces the effective observing time available for scientific programs, increases the cost of research, and can make certain types of observations impossible during times when satellite density is highest. The problem gets worse as more constellations launch, because each new constellation adds its own contribution to the cumulative noise floor, and there's no mechanism currently in place to coordinate emissions across different operators to minimize the total impact on radio astronomy.

The Satellite Operator's Perspective: Constraints and Realities

Satellite operators face real engineering and economic constraints that make reducing unintended emissions more complex than it might appear at first glance. Every additional gram of shielding, every extra filter, and every design change that reduces emissions also adds mass, cost, and complexity to a satellite that needs to be manufactured at scale and launched economically. When you're building thousands of satellites for a constellation, even small per-unit cost increases multiply quickly, and mass is particularly expensive because it directly affects launch costs. Operators also need to balance emission control against other design priorities like power efficiency, thermal management, and reliability, and the tradeoffs aren't always straightforward. A power supply design that reduces switching noise might also be less efficient, requiring larger solar panels and batteries, which increases mass and cost in a different way.

Regulatory compliance adds another layer of complexity. Satellite operators must coordinate with multiple national regulatory bodies, comply with ITU Radio Regulations, and navigate different national rules that can vary significantly between countries. The FCC Part 25 9 rules for satellite services establish limits on out-of-band and spurious emissions, but these limits are designed to prevent interference with other communication services, not to protect radio astronomy's extreme sensitivity requirements. An operator can be fully compliant with Part 25 and still generate emissions that affect radio telescopes, because the regulatory framework wasn't designed to account for the cumulative effects of large constellations on radio astronomy observations. This creates a situation where operators are following the rules as written, but the rules themselves don't fully address the problem that radio astronomers are experiencing.

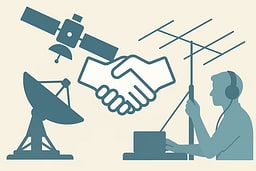

The good news is that some operators are already taking voluntary steps to reduce their impact on astronomy, even beyond what regulations require. SpaceX has worked with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) 10 to develop coordination protocols that allow satellites to adjust their operations during sensitive observations, and the company has implemented design changes to reduce optical brightness for ground-based optical astronomy. These voluntary measures demonstrate that cooperation is possible and that operators can find engineering solutions when the problem is clearly defined and the collaboration is structured effectively. The challenge is scaling these cooperative efforts across all operators and making them systematic rather than ad-hoc, which requires better coordination frameworks, clearer technical standards, and more consistent regulatory guidance that accounts for both the needs of satellite services and the protection of radio astronomy. Building these frameworks is where the real work happens, and it's where individuals and organizations can make a meaningful difference.

Why This Matters to Amateur Radio Operators

As an amateur radio operator, I've spent years learning about spectrum discipline, spurious emission control, and the importance of keeping our signals clean. The FCC teaches these principles through Part 97 regulations, licensing exams, and the culture of the amateur radio community itself. We're taught to use proper filtering, maintain our equipment to minimize spurious emissions, and always operate within our authorized frequency allocations. When we cause interference, even unintentionally, we're expected to fix it immediately, and the community self-polices these standards because we understand that spectrum is a shared resource. The contrast between this rigorous approach to amateur radio emissions and the current state of satellite constellation emissions is what caught my attention when I read the LOFAR study—it's the same fundamental problem of unintended radiation, but the regulatory and cultural response seems different.

The connection between amateur radio practices and radio astronomy protection is more direct than it might appear. The same engineering principles that keep our stations from interfering with public safety channels or neighboring amateur operators are the same principles that need to be applied at scale to satellite hardware. Proper RF shielding, careful filtering of digital clock signals, attention to grounding and bonding, and design practices that minimize unintended radiation are all things we learn as amateur operators, and they're all relevant to reducing satellite emissions. The difference is that amateur radio operators are individuals who can be directly regulated and educated, while satellite constellations are large-scale commercial operations with different economic incentives and regulatory frameworks. But the underlying physics and engineering solutions are the same, which means amateur radio operators are well-positioned to understand the problem and advocate for solutions.

Amateur radio operators also have a unique perspective on spectrum management because we operate across a wide range of frequencies and interact with multiple services. We understand how interference affects different types of operations, we've experienced the frustration of trying to work weak signals when the noise floor is high, and we know what it takes to maintain clean emissions from our own equipment. This practical experience gives us credibility when discussing spectrum issues with regulators, policymakers, and the general public. We can explain why clean signals matter, how unintended emissions occur, and what engineering solutions actually work in practice, because we've had to solve these problems ourselves. This makes amateur radio operators valuable advocates for protecting radio astronomy, not because we're directly affected by satellite emissions in the same way astronomers are, but because we understand the technical and regulatory landscape and can help bridge the gap between different communities that all depend on shared spectrum resources.

The rising noise floor is something amateur radio operators have been experiencing for decades, and it's getting worse. Consumer electronics, LED lighting, switching power supplies, Wi-Fi routers, Bluetooth devices, and countless other RF-emitting gadgets have steadily increased the background noise across amateur bands. For operators running low-power stations—QRP operators who might transmit with just a few watts or less—this rising noise floor can make the difference between making a contact and not being heard at all. What used to be a workable signal-to-noise ratio on 20 meters or 40 meters can become impossible when the noise floor rises by just a few decibels, because those operators are already operating near the limits of what's detectable. Radio astronomers face the same fundamental problem, just at a different scale—they're trying to detect signals that are millions of times weaker than typical communication signals, and every decibel of additional noise floor makes their work harder. The proliferation of satellite constellations adds another layer to this problem, because each satellite contributes its own small amount of unintended radiation, and when you multiply that by thousands of satellites, the cumulative effect becomes significant. Both communities are fighting the same battle against a rising noise floor, and both need the same thing: better emission control from all sources, whether terrestrial or orbital.

Engineering Pathways Toward Solutions

The technical solutions for reducing unintended satellite emissions exist—they're the same RF engineering practices used in other applications where emission control is critical. Improved internal grounding and bonding can reduce common-mode currents that radiate from power and signal cables. Better shielding of switching power supplies, digital clock circuits, and high-speed data buses can contain emissions at their source. Tighter RF filtering on internal clocks and data lines can prevent harmonics and spurious signals from reaching external antennas or radiating from the satellite structure itself. These aren't theoretical solutions—they're standard practices in military, aerospace, and medical equipment where emission control is a design requirement, and they can be adapted for commercial satellite constellations with appropriate engineering effort and cost analysis.

The challenge isn't that solutions don't exist, but that implementing them at constellation scale requires coordination, standards, and economic incentives that don't currently align perfectly. Satellite operators need clear technical specifications that define acceptable emission levels for radio astronomy protection, because "as low as reasonably achievable" means different things to different engineers without specific targets. Radio astronomers need better coordination protocols that allow observatories to communicate observation schedules to operators, so satellites can adjust operations during critical observing windows. Regulators need updated frameworks that account for cumulative effects of multiple constellations, not just individual satellite compliance. And all of these pieces need to work together in a way that doesn't create excessive burden on any single stakeholder, because solutions that are technically perfect but economically or operationally impractical won't be adopted.

Some of this coordination is already happening. The SETI Institute and SpaceX collaboration 13 demonstrates that operators and astronomers can work together when the framework is structured correctly. The NRAO coordination system shows that data sharing between observatories and satellite operators can reduce interference during sensitive observations. The IAU Centre for the Protection of Dark & Quiet Skies 3 provides a forum for ongoing dialogue between all stakeholders. These are positive steps, but they need to become more systematic, more widely adopted, and more integrated into the regulatory process. The engineering solutions are ready—what we need now is better coordination frameworks, clearer standards, and more consistent application of best practices across all operators and all observatories. This is where individual action and advocacy can make a real difference, because building these frameworks requires support from the communities that care about both satellite connectivity and scientific discovery.

What You Can Do: Concrete Steps to Help Quiet the Sky

The noise floor keeps rising as more satellites launch, but that doesn't mean we're powerless to address it. There are concrete, actionable steps that individuals and organizations can take to support better spectrum management and protect radio astronomy, and they don't require becoming a regulatory expert or an RF engineer. The key is understanding that this is a coordination and awareness problem as much as it is a technical problem, and that building better frameworks requires support from people who care about both connectivity and scientific discovery. Here's what you can actually do, starting today, to make a difference.

If you're an amateur radio operator, you're already part of a community that understands spectrum discipline and emission control. Use that knowledge to advocate for better satellite emission standards in your local clubs, at hamfests, and in conversations with other operators. Contact the ARRL 4 to express support for spectrum protection initiatives, and share information about the radio astronomy interference problem with operators who might not be aware of it. Your practical experience with RF engineering and emission control gives you credibility when discussing these issues, and the amateur radio community has a long history of effective advocacy on spectrum matters. You can also lead by example—ensure your own station operates with minimal spurious emissions, document your practices, and share what you learn with others. The same engineering principles that keep your station clean are the principles that need to be applied at scale to satellite constellations, and demonstrating those principles in practice helps make the case for why they matter.

If you're a satellite internet user, you have a direct relationship with the operators who can implement emission reductions, and your voice as a customer matters. If you're a Starlink customer, you can contact SpaceX through their support channels to express your support for improved satellite shielding and emission control. Mention that you value both reliable internet connectivity and scientific discovery, and that you'd like to see continued improvements in RF shielding, better filtering of onboard electronics, and ongoing collaboration with radio observatories. You can also reach out through SpaceX's public communications channels or participate in customer feedback surveys to make spectrum protection a visible customer priority. For other satellite internet providers, use the same approach—contact customer support, ask about their emission mitigation efforts, and express support for continued collaboration with radio astronomy organizations. Many operators are already working with astronomers voluntarily, but they need to know that customers value these efforts and want them to continue and expand. You can also support organizations like the IAU Centre for the Protection of Dark & Quiet Skies 3 that facilitate coordination between operators and astronomers, and share information about the issue with other users who might not be aware of the radio astronomy impact. When enough customers express concern about spectrum protection, it creates economic incentives for operators to invest in better emission control as a competitive advantage and a demonstration of responsible engineering.

If you're a developer or engineer, you can contribute technical expertise to the coordination efforts. Radio observatories need help building data sharing systems, interference prediction tools, and coordination protocols that allow real-time communication with satellite operators. The SKA Observatory 11 and other major facilities have ongoing projects that need software engineering support, and contributing to open-source tools for interference mitigation is a concrete way to help. You can also advocate within your own organization if you work in aerospace, telecommunications, or related fields, because the engineering solutions for emission reduction often come from the same companies that build satellites. If your company is involved in satellite operations or manufacturing, push for emission control to be a design requirement, not an afterthought, and support collaboration with radio astronomy organizations. The technical community has the skills to solve this problem—we just need to apply them systematically.

If you're a concerned citizen, you can raise awareness and support policy initiatives. Contact your representatives to express support for updated regulations that account for cumulative satellite emissions and radio astronomy protection, and share information about the issue on social media and in community discussions. Support organizations that work on spectrum protection, such as the National Radio Astronomy Observatory 10 and the Green Bank Observatory 12, which depend on public support to continue their research and advocacy work. You can also participate in public comment periods when regulatory bodies like the FCC consider spectrum allocation changes or satellite licensing decisions, because public input influences regulatory priorities. The most important thing you can do is stay informed and share accurate information—this isn't about opposing satellite connectivity, but about ensuring that connectivity and scientific discovery can coexist through better coordination and engineering practices.

If you're a researcher or student, you can contribute to the scientific understanding of the interference problem and develop better mitigation techniques. The LOFAR study that detected the Starlink emissions is exactly the kind of research that needs to continue, because we need ongoing monitoring to understand how interference changes as constellations grow and new operators launch satellites. You can also work on signal processing techniques that help radio telescopes identify and filter interference more effectively, coordination algorithms that optimize satellite operations around observation schedules, and engineering solutions that reduce emissions at the source. Research institutions and observatories often have internship programs, collaboration opportunities, and open research questions that students and researchers can contribute to, and building a career around spectrum protection and radio astronomy is a meaningful way to address this problem long-term. The scientific community needs more people working on these challenges, and if you're interested in RF engineering, signal processing, or astronomy, this is an area where your skills can make a real difference.

Building a Framework for Cooperation

The fundamental challenge here isn't technical—it's organizational. We have the engineering knowledge to reduce unintended satellite emissions, we have observatories that can coordinate with operators, and we have regulatory frameworks that can be updated to account for modern constellation operations. What we're missing is systematic coordination that brings all these pieces together consistently across all operators, all observatories, and all regulatory jurisdictions. Building that coordination framework requires support from everyone who benefits from both satellite connectivity and scientific discovery, because it won't happen automatically—it needs to be constructed through deliberate effort, clear communication, and sustained advocacy.

The good news is that we're not starting from zero. The voluntary coordination efforts between SpaceX and NRAO, the IAU Centre's work on bringing stakeholders together, and the ongoing research that documents the interference problem all provide foundations that can be built upon. What's needed now is to make these efforts more systematic, more widely adopted, and more integrated into standard operating procedures for both satellite operators and radio observatories. This requires policy support, technical standards, economic incentives, and cultural change within the industries involved, and all of those things are achievable if enough people care enough to push for them. The noise floor is rising, but it doesn't have to rise indefinitely—we can build frameworks that allow satellite connectivity and radio astronomy to coexist, provided we're willing to put in the work to make that happen.

This isn't about choosing between connectivity and science—it's about ensuring both can thrive through better engineering, better coordination, and better awareness of how our technological choices affect the shared resource of the radio spectrum. As someone who values both reliable internet access and scientific discovery, I believe we can have both, but only if we're intentional about building the cooperation frameworks that make it possible. The sky doesn't have to get noisier forever, and every person who takes action to support spectrum protection, whether through advocacy, technical contribution, or simply raising awareness, helps move us toward solutions that work for everyone. The universe is trying to tell us something—we just need to make sure we can still hear it over the noise we're creating ourselves.

References

[1] Wijers, R. A. M. J., et al. (2024). Bright unintended electromagnetic radiation from second-generation Starlink satellites. Astronomy & Astrophysics.

[2] LOFAR (Low-Frequency Array for Radio Astronomy).

[3] IAU Centre for the Protection of Dark & Quiet Skies.

[4] ARRL Regulatory & Advocacy.

[5] International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Radio Regulations.

[6] ITU-R Recommendation RA.769: Protection criteria used for radio astronomical measurements.

[7] ITU-R Recommendation SM.1541: Unwanted emissions in the spurious domain.

[8] FCC Part 97: Amateur Radio Service Rules.

[9] FCC Part 25: Satellite Communications.

[10] National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO).

[11] Square Kilometer Array (SKA) Observatory.

[13] SETI Institute and SpaceX Collaboration on Radio Astronomy Protection.

[14] Very Large Array (VLA) - National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

About Joshua Morris

Joshua is a software engineer focused on building practical systems and explaining complex ideas clearly.