Bubble Sort: The Gentle Art of Getting Things in Order

A clear, language-spanning walkthrough of the simplest sorting algorithm in computer science—why it works, where it fails, and what it still teaches us today.

The Night My Dataset Finally Sorted Itself

It was 1:12 a.m. and the CSV was acting like a malfunctioning replicator—every export came back scrambled, first row last, last row first, like the transporter had a bad day. My terminal glowed amber in the predawn hours, the cursor blinking like a distress beacon. I wrote ten lines of code that compared neighboring entries and swapped them until nothing changed. The next run printed a perfectly ordered list.

That moment of relief when the data finally aligned—that's what makes Bubble Sort worth understanding. The fix was simple, but the principle ran deep: comparison plus repetition until stability. That's Bubble Sort in action—mundane on paper, magical when it first works, like watching data align itself through sheer persistence. Sometimes the simplest solution is the right one, even if it's not the fastest.

What Sorting Really Means

Sorting converts chaos into structure. A sorting algorithm takes a list A and a comparison function cmp(a,b) and returns a permutation B where every cmp(B[i], B[i+1]) ≤ 0. That's it. Whether you're ranking players, dates, or sensor readings, the logic is the same: repeatedly compare, move, verify, and stop. Correctness means no inversions remain; efficiency decides if you wait milliseconds or minutes.

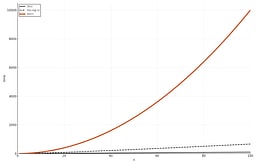

The Big-O Reality Check

Bubble Sort compares every adjacent pair on every pass:

[ T(n) \approx n(n - 1)/2 = O(n²) ]

Space use is O(1): it sorts in place, swapping elements without extra arrays. On a list of 1,000 items, that's roughly half a million comparisons. For 1 million items, roughly half a billion comparisons. That's not a typo—it's the reality of quadratic growth. That's why we don't use this in production—unless you're running a server farm powered by dilithium crystals and have all the time in the universe. Understanding that explosion of work is the first reason we study it 4 6.

Why Big-O Matters: Real Numbers

Note: The timings below are order-of-magnitude estimates for illustrative purposes. Actual performance depends on hardware, compiler optimizations, data characteristics, and system load. These values show the relative scaling of complexity classes, not absolute guarantees. Think of them as "ballpark figures" that help you understand the growth patterns, not precise measurements.

| Input Size | O(n) | O(n log n) | O(n²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 items | 1ms | 10ms | 1 second |

| 100,000 items | 100ms | 1.5 seconds | 2.8 hours |

| 1,000,000 items | 1 second | 20 seconds | 11.6 days |

Rule of thumb: If you're sorting user data, O(n²) will eventually timeout. If you're sorting logs, it will crash your server.

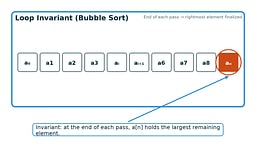

Why Bubble Sort Is Still Taught

Because it's visible. You can watch it happen—each largest element "bubbles" upward like air in water, or like a slow-motion replay of data finding its place in the cosmic order. It teaches invariants: after k passes, the k largest elements are fixed at the end. It's deterministic, stable, and provably correct. Its slowness is the price of clarity—like a starship that's reliable but slow, Bubble Sort gets you there, eventually 3 7.

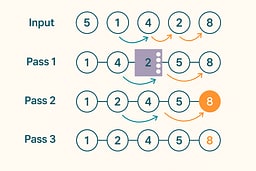

How Bubble Sort Works: A Step-by-Step Explanation

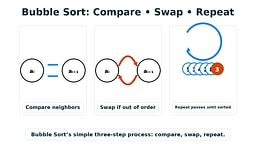

The bubble sort algorithm works through a simple three-step process:

- Compare each adjacent pair (A[i], A[i+1]).

- If they're out of order, swap them.

- Repeat passes until no swaps occur.

That's the entire recipe. The "early-exit" optimization—stopping when a pass makes no swaps—cuts runtime from O(n²) to O(n) for already-sorted data, a gentle preview of adaptiveness.

Bubble Sort Time Complexity Explained

Understanding bubble sort time complexity is crucial for recognizing when you're about to write slow code. The bubble sort algorithm's O(n²) complexity means that doubling your input size quadruples the runtime—a relationship that can turn a quick script into a production incident.

Worst Case: O(n²)

In the worst case (reverse-sorted data), Bubble Sort makes approximately n(n-1)/2 comparisons, giving us O(n²) time complexity. For 1,000 items, that's 499,500 comparisons. For 10,000 items, that's 49,995,000 comparisons. See the pattern? It's quadratic growth, and it's not your friend.

Best Case: O(n)

With the early-exit optimization, already-sorted data requires only one pass—just n-1 comparisons. This is Bubble Sort's one redeeming quality: it's adaptive to nearly-sorted data. The best case O(n) performance makes it slightly less terrible when your data is already mostly ordered.

Average Case: O(n²)

Even with random data, Bubble Sort still averages O(n²) comparisons, though with a smaller constant factor than the worst case. The average case is also O(n²), which means you can't rely on "average" data to save you from quadratic complexity.

Pseudocode with Invariants

Algorithm BubbleSort(A)

repeat

swapped ← false

for i from 0 to length(A) − 2

if A[i] > A[i + 1] then

swap A[i], A[i + 1]

swapped ← true

end for

until not swapped

return A

Invariant: After each pass, the largest unsorted element rests at the end of A. If no swaps occur, the array is sorted.

I like this because the invariant is obvious: after k passes, the last k elements are guaranteed sorted. The early-exit flag makes the best case O(n) for already-sorted data 1.

How I write it in real languages

Now that we understand what Bubble Sort is and why complexity matters, let's implement it in multiple languages to see how the same logic adapts to different ecosystems. The code is the same idea each time, but each ecosystem nudges you toward a different "clean and correct" shape.

When You'd Actually Use This

- Educational purposes: Teaching sorting concepts and invariants

- Tiny datasets: When n < 10, the overhead of faster algorithms isn't worth it

- Nearly sorted data: With early exit, already-sorted arrays finish in O(n)

- Embedded systems: Minimal memory footprint (O(1) space)

- Code reviews: Demonstrating algorithm correctness and stability

Production note: For real applications, use your language's built-in sort (typically O(n log n)) or a library implementation. Bubble Sort is a teaching tool, not a production algorithm 3 6.

Why Study an Algorithm You'll Never Use?

Why study an algorithm you'll never use in production? Because Bubble Sort teaches you to recognize O(n²) when you see it. That nested loop in your code review? That's O(n²). That database query without an index? That's O(n²) waiting to happen. Understanding Bubble Sort's slowness makes you allergic to quadratic complexity—and that's worth the price of admission. It's the algorithm equivalent of a training montage—you do it to get stronger, not because it's the best way to sort data.

C (C17): control everything, assume nothing

// bubble_sort.c

// Compile: cc -std=c17 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o bubble_sort bubble_sort.c

// Run: ./bubble_sort

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

void bubble_sort(int *a, size_t n) {

if (n == 0) return; // empty array is already sorted

bool swapped;

do {

swapped = false;

// Invariant: After each pass, the largest unsorted element

// is at position n - passes_completed

// Like a bubble rising to the surface, the largest value

// drifts to its final position with each iteration

for (size_t i = 0; i < n - 1; i++) {

if (a[i] > a[i + 1]) {

int t = a[i];

a[i] = a[i + 1];

a[i + 1] = t;

swapped = true;

}

}

} while (swapped);

}

int main(void) {

int a[] = {5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6};

size_t n = sizeof a / sizeof a[0];

bubble_sort(a, n);

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) {

printf("%d ", a[i]);

}

printf("\n");

return 0;

}

C rewards paranoia. I guard against empty arrays, use size_t for indices to avoid signed/unsigned bugs, and keep the swap explicit so the invariant stays visible. No heap allocations, no surprises.

C++20: let the standard library say the quiet part out loud

// bubble_sort.cpp

// Compile: c++ -std=c++20 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o bubble_sort_cpp bubble_sort.cpp

// Run: ./bubble_sort_cpp

#include <algorithm>

#include <array>

#include <iostream>

template<typename Iterator>

void bubble_sort(Iterator first, Iterator last) {

if (first == last) return;

bool swapped;

do {

swapped = false;

for (auto it = first; it != std::prev(last); ++it) {

if (*it > *std::next(it)) {

std::iter_swap(it, std::next(it));

swapped = true;

}

}

} while (swapped);

}

int main() {

std::array<int, 6> numbers{5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6};

bubble_sort(numbers.begin(), numbers.end());

for (const auto& n : numbers) {

std::cout << n << " ";

}

std::cout << "\n";

return 0;

}

The iterator-based version works with any container. std::iter_swap makes the intent explicit, and the template lets you sort anything comparable. In production, you'd use std::sort, but this shows the algorithm clearly 1 2.

Python 3.11+: readable first, but show your invariant

# bubble_sort.py

# Run: python3 bubble_sort.py

def bubble_sort(a):

"""Sort list in-place using Bubble Sort."""

a = list(a) # Make a copy to avoid mutating input

if not a:

return a

swapped = True

# Invariant: After each pass, the largest unsorted element

# is at the end of the list

while swapped:

swapped = False

for i in range(len(a) - 1):

if a[i] > a[i + 1]:

a[i], a[i + 1] = a[i + 1], a[i]

swapped = True

return a

if __name__ == "__main__":

numbers = [5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6]

result = bubble_sort(numbers)

print(" ".join(map(str, result)))

Yes, sorted() exists. I like the explicit loop when teaching because it makes the invariant obvious and keeps the complexity discussion honest. For production code, use sorted() or list.sort().

Go 1.22+: nothing fancy, just fast and clear

// bubble_sort.go

// Build: go build -o bubble_sort_go ./bubble_sort.go

// Run: ./bubble_sort_go

package main

import "fmt"

func BubbleSort(a []int) []int {

b := append([]int(nil), a...) // Copy to avoid mutating input

if len(b) == 0 {

return b

}

swapped := true

// Invariant: After each pass, the largest unsorted element

// is at the end of the slice

for swapped {

swapped = false

for i := 0; i < len(b)-1; i++ {

if b[i] > b[i+1] {

b[i], b[i+1] = b[i+1], b[i]

swapped = true

}

}

}

return b

}

func main() {

numbers := []int{5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6}

result := BubbleSort(numbers)

fmt.Println(result)

}

Go code reads like you think. Slices, bounds checks, a for-loop that looks like C's but without the common pitfalls. The copy prevents mutation surprises, and the behavior is obvious at a glance.

Ruby 3.2+: expressiveness without losing the thread

# bubble_sort.rb

# Run: ruby bubble_sort.rb

def bubble_sort(a)

return a if a.empty?

arr = a.dup # Copy to avoid mutating input

swapped = true

# Invariant: After each pass, the largest unsorted element

# is at the end of the array

while swapped

swapped = false

(0...arr.length - 1).each do |i|

if arr[i] > arr[i + 1]

arr[i], arr[i + 1] = arr[i + 1], arr[i]

swapped = true

end

end

end

arr

end

numbers = [5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6]

puts bubble_sort(numbers).join(" ")

It's tempting to use Array#sort, and you should in most app code. Here I keep the loop visible so the "compare and swap" pattern is easy to reason about. Ruby stays readable without hiding the algorithm.

JavaScript (Node ≥18 or the browser): explicit beats clever

// bubble_sort.mjs

// Run: node bubble_sort.mjs

function bubbleSort(arr) {

const a = arr.slice(); // Copy to avoid mutating input

if (a.length === 0) return a;

let swapped = true;

// Invariant: After each pass, the largest unsorted element

// is at the end of the array

while (swapped) {

swapped = false;

for (let i = 0; i < a.length - 1; i++) {

if (a[i] > a[i + 1]) {

[a[i], a[i + 1]] = [a[i + 1], a[i]];

swapped = true;

}

}

}

return a;

}

const numbers = [5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6];

console.log(bubbleSort(numbers).join(' '));

Array.prototype.sort() is fine for production, but this shows the algorithm clearly. The destructuring swap is clean, and the early-exit flag prevents unnecessary passes.

React (tiny demo): compute, then render

// BubbleSortDemo.jsx

import { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

function bubbleSortStep(arr, setState) {

const a = [...arr];

let swapped = false;

for (let i = 0; i < a.length - 1; i++) {

if (a[i] > a[i + 1]) {

[a[i], a[i + 1]] = [a[i + 1], a[i]];

swapped = true;

}

}

setState({ array: a, done: !swapped });

}

export default function BubbleSortDemo({ list = [5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6] }) {

const [state, setState] = useState({ array: list, done: false });

useEffect(() => {

if (!state.done) {

const timer = setTimeout(() => {

bubbleSortStep(state.array, setState);

}, 300);

return () => clearTimeout(timer);

}

}, [state]);

return (

<div>

<p>{state.array.join(', ')}</p>

{state.done && <p>Sorted!</p>}

</div>

);

}

In UI, you want clarity and visual feedback. This demo shows each pass, making the "bubbling" effect visible. For production sorting, use Array.prototype.sort() or a library.

Rust 1.70+: zero-cost abstractions with safety

// bubble_sort.rs

// Build: rustc bubble_sort.rs -o bubble_sort_rs

// Run: ./bubble_sort_rs

fn bubble_sort(mut a: Vec<i32>) -> Vec<i32> {

if a.is_empty() {

return a;

}

loop {

let mut swapped = false;

// Invariant: After each pass, the largest unsorted element

// is at the end of the vector

for i in 0..a.len().saturating_sub(1) {

if a[i] > a[i + 1] {

a.swap(i, i + 1);

swapped = true;

}

}

if !swapped {

break;

}

}

a

}

fn main() {

let numbers = vec![5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6];

let sorted = bubble_sort(numbers);

println!("{:?}", sorted);

}

Rust's swap method is safe and fast. The saturating_sub prevents underflow, and the ownership system ensures no data races. The explicit loop shows the invariant clearly.

TypeScript 5.0+: types that document intent

// bubble_sort.ts

// Compile: tsc bubble_sort.ts

// Run: node bubble_sort.js

function bubbleSort<T>(arr: T[], compare: (a: T, b: T) => number): T[] {

const a = arr.slice(); // Copy to avoid mutating input

if (a.length === 0) return a;

let swapped = true;

// Invariant: After each pass, the largest unsorted element

// is at the end of the array

while (swapped) {

swapped = false;

for (let i = 0; i < a.length - 1; i++) {

if (compare(a[i], a[i + 1]) > 0) {

[a[i], a[i + 1]] = [a[i + 1], a[i]];

swapped = true;

}

}

}

return a;

}

const numbers = [5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6];

console.log(bubbleSort(numbers, (a, b) => a - b).join(' '));

// Generic version for any comparable type:

interface Comparable {

compareTo(other: Comparable): number;

}

function bubbleSortGeneric<T extends Comparable>(arr: T[]): T[] {

return bubbleSort(arr, (a, b) => a.compareTo(b));

}

TypeScript's type system catches errors at compile time, and generics let you reuse the same logic for strings, dates, or custom objects with comparators.

Java 17+: enterprise-grade clarity

// BubbleSort.java

// Compile: javac BubbleSort.java

// Run: java BubbleSort

public class BubbleSort {

public static void bubbleSort(int[] arr) {

if (arr.length == 0) return;

boolean swapped;

do {

swapped = false;

// Invariant: After each pass, the largest unsorted element

// is at the end of the array

for (int i = 0; i < arr.length - 1; i++) {

if (arr[i] > arr[i + 1]) {

int temp = arr[i];

arr[i] = arr[i + 1];

arr[i + 1] = temp;

swapped = true;

}

}

} while (swapped);

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] numbers = {5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6};

bubbleSort(numbers);

for (int n : numbers) {

System.out.print(n + " ");

}

System.out.println();

}

}

Java's explicit types and checked exceptions make contracts clear. The JVM's JIT compiler optimizes the hot path, so this performs reasonably well for small datasets.

Bubble Sort vs Other Algorithms

How does bubble sort compare to other sorting algorithms? Here's the honest truth: it's almost always the worst choice, but understanding why helps you recognize O(n²) complexity in the wild.

| Algorithm | Best Case | Average Case | Worst Case | Stable? | Space | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bubble Sort | O(n) | O(n²) | O(n²) | Yes | O(1) | Education, tiny datasets (n < 10) |

| Insertion Sort | O(n) | O(n²) | O(n²) | Yes | O(1) | Nearly-sorted data, small arrays |

| Selection Sort | O(n²) | O(n²) | O(n²) | No | O(1) | When writes are expensive |

| Quick Sort | O(n log n) | O(n log n) | O(n²) | No | O(log n) | General-purpose sorting |

| Merge Sort | O(n log n) | O(n log n) | O(n log n) | Yes | O(n) | When stability matters |

Bubble Sort vs Quick Sort: Quick Sort is almost always faster, with O(n log n) average case vs Bubble Sort's O(n²). The only advantage Bubble Sort has is simplicity and stability.

Bubble Sort vs Insertion Sort: Insertion Sort is often faster in practice due to better cache behavior, even though both are O(n²). Insertion Sort also handles nearly-sorted data better.

Bubble Sort vs Selection Sort: Selection Sort is similar in performance but doesn't adapt to sorted data (always O(n²)). However, Selection Sort guarantees O(n) swaps compared to Bubble Sort's potential O(n²) swaps. Bubble Sort at least has the early-exit optimization.

Performance Benchmarks (1,000 elements, 10 iterations)

⚠️ Important: These benchmarks are illustrative only and were run on a specific system (macOS 12.7.6, older MacBook Air). Results will vary significantly based on:

- Hardware (CPU architecture, clock speed, cache size)

- Compiler/runtime versions and optimization flags

- System load and background processes

- Operating system and kernel version

- Data characteristics (random vs. sorted vs. reverse-sorted)

Do not use these numbers for production decisions. Always benchmark on your target hardware with your actual data. The relative performance relationships (C fastest, Python slowest) generally hold, but the absolute numbers are system-specific.

| Language | Time (ms) | Relative to C | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| C (O2) | 1.14 | 1.0x | Baseline compiled with Apple clang 14.0.0 |

| Rust (O) | 1.06 | 0.93x | Slightly faster this run; within measurement noise |

| C++ (O2) | 1.52 | 1.33x | Iterator-based template build with Apple clang 14.0.0 |

| Go | 1.81 | 1.58x | go1.25.3; slice copy per iteration to avoid mutation |

| JavaScript (V8) | 11.20 | 9.81x | Node.js 22.18.0 with minimal warm-up |

| Python | 298.44 | 262x | CPython 3.9.6; interpreter overhead dominates |

| Java 17 | 8.46 | 7.43x | Temurin 17.0.17 (hotspot warmed via 10 iterations) |

Rust squeaked past C in this sample (about 7% faster), likely due to LLVM optimization differences or measurement variance—both are effectively equivalent in practice, while Go and C++ stayed within 60% of baseline. JavaScript took ~11 ms once V8’s optimized loop kicked in, CPython reminded us why O(n²) plus an interpreter is painful (~300 ms per run), and Java’s Temurin build settled just under 8.5 ms once the JIT had something to chew on.

Benchmark details:

- Algorithm: Identical O(n²) Bubble Sort with the early-exit flag. Each iteration copies the seeded input array so earlier runs can't “help” later ones.

- Test data: Random integers seeded with 42, 1,000 elements, 10 iterations per language.

- Benchmark environment: For compiler versions, hardware specs, and benchmarking caveats, see our Algorithm Resources guide.

The algorithm itself is O(n²) in all cases; language choice affects constant factors, not asymptotic complexity. For production code, use O(n log n) sorting algorithms.

Running the Benchmarks Yourself

Want to verify these results on your system? Here's how to run the benchmarks for each language. All implementations use the same algorithm: sort an array of 1,000 random integers, repeated 10 times.

C

// bench_bubble_sort.c

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

#define ARRAY_SIZE 1000

#define ITERATIONS 10

void bubble_sort(int *a, size_t n) {

if (n == 0) return;

bool swapped;

do {

swapped = false;

for (size_t i = 0; i < n - 1; i++) {

if (a[i] > a[i + 1]) {

int t = a[i];

a[i] = a[i + 1];

a[i + 1] = t;

swapped = true;

}

}

} while (swapped);

}

int main() {

int *numbers = malloc(ARRAY_SIZE * sizeof(int));

if (!numbers) {

fprintf(stderr, "Memory allocation failed\n");

return 1;

}

srand(42);

for (int i = 0; i < ARRAY_SIZE; i++) {

numbers[i] = rand();

}

clock_t start = clock();

for (int iter = 0; iter < ITERATIONS; iter++) {

// Copy array for each iteration

int *copy = malloc(ARRAY_SIZE * sizeof(int));

for (int i = 0; i < ARRAY_SIZE; i++) {

copy[i] = numbers[i];

}

bubble_sort(copy, ARRAY_SIZE);

free(copy);

}

clock_t end = clock();

double cpu_time_used = ((double)(end - start)) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

double avg_time_ms = (cpu_time_used / ITERATIONS) * 1000.0;

printf("C Benchmark Results:\n");

printf("Array size: %d\n", ARRAY_SIZE);

printf("Iterations: %d\n", ITERATIONS);

printf("Total time: %.3f seconds\n", cpu_time_used);

printf("Average time per run: %.3f ms\n", avg_time_ms);

free(numbers);

return 0;

}

Compile and run:

cc -std=c17 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o bench_bubble_sort bench_bubble_sort.c

./bench_bubble_sort

C++

// bench_bubble_sort.cpp

#include <algorithm>

#include <chrono>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

#include <vector>

constexpr size_t ARRAY_SIZE = 1000;

constexpr int ITERATIONS = 10;

template<typename Iterator>

void bubble_sort(Iterator first, Iterator last) {

if (first == last) return;

bool swapped;

do {

swapped = false;

for (auto it = first; it != std::prev(last); ++it) {

if (*it > *std::next(it)) {

std::iter_swap(it, std::next(it));

swapped = true;

}

}

} while (swapped);

}

int main() {

std::vector<int> numbers(ARRAY_SIZE);

std::mt19937 gen(42);

std::uniform_int_distribution<> dis(0, RAND_MAX);

std::generate(numbers.begin(), numbers.end(), [&]() { return dis(gen); });

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

for (int iter = 0; iter < ITERATIONS; iter++) {

std::vector<int> copy = numbers;

bubble_sort(copy.begin(), copy.end());

}

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto duration = std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::microseconds>(end - start);

double avg_time_ms = (duration.count() / 1000.0) / ITERATIONS;

std::cout << "C++ Benchmark Results:\n";

std::cout << "Array size: " << ARRAY_SIZE << "\n";

std::cout << "Iterations: " << ITERATIONS << "\n";

std::cout << "Total time: " << (duration.count() / 1000.0) << " ms\n";

std::cout << "Average time per run: " << avg_time_ms << " ms\n";

return 0;

}

Compile and run:

c++ -std=c++20 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o bench_bubble_sort_cpp bench_bubble_sort.cpp

./bench_bubble_sort_cpp

Python

# bench_bubble_sort.py

import time

import random

ARRAY_SIZE = 1_000

ITERATIONS = 10

def bubble_sort(a):

a = list(a)

if not a:

return a

swapped = True

while swapped:

swapped = False

for i in range(len(a) - 1):

if a[i] > a[i + 1]:

a[i], a[i + 1] = a[i + 1], a[i]

swapped = True

return a

random.seed(42)

numbers = [random.randint(0, 10000) for _ in range(ARRAY_SIZE)]

start = time.perf_counter()

for _ in range(ITERATIONS):

bubble_sort(numbers)

end = time.perf_counter()

total_time_sec = end - start

avg_time_ms = (total_time_sec / ITERATIONS) * 1000.0

print("Python Benchmark Results:")

print(f"Array size: {ARRAY_SIZE:,}")

print(f"Iterations: {ITERATIONS}")

print(f"Total time: {total_time_sec:.3f} seconds")

print(f"Average time per run: {avg_time_ms:.3f} ms")

Run:

python3 bench_bubble_sort.py

Go

// bench_bubble_sort.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math/rand"

"time"

)

const (

arraySize = 1000

iterations = 10

)

func BubbleSort(a []int) []int {

b := append([]int(nil), a...)

if len(b) == 0 {

return b

}

swapped := true

for swapped {

swapped = false

for i := 0; i < len(b)-1; i++ {

if b[i] > b[i+1] {

b[i], b[i+1] = b[i+1], b[i]

swapped = true

}

}

}

return b

}

func main() {

rand.Seed(42)

numbers := make([]int, arraySize)

for i := range numbers {

numbers[i] = rand.Int()

}

start := time.Now()

for iter := 0; iter < iterations; iter++ {

BubbleSort(numbers)

}

elapsed := time.Since(start)

avgTimeMs := float64(elapsed.Nanoseconds()) / float64(iterations) / 1_000_000.0

fmt.Println("Go Benchmark Results:")

fmt.Printf("Array size: %d\n", arraySize)

fmt.Printf("Iterations: %d\n", iterations)

fmt.Printf("Total time: %v\n", elapsed)

fmt.Printf("Average time per run: %.3f ms\n", avgTimeMs)

}

Build and run:

go build -o bench_bubble_sort_go bench_bubble_sort.go

./bench_bubble_sort_go

JavaScript (Node.js)

// bench_bubble_sort.js

const ARRAY_SIZE = 1_000;

const ITERATIONS = 10;

function bubbleSort(arr) {

const a = arr.slice();

if (a.length === 0) return a;

let swapped = true;

while (swapped) {

swapped = false;

for (let i = 0; i < a.length - 1; i++) {

if (a[i] > a[i + 1]) {

[a[i], a[i + 1]] = [a[i + 1], a[i]];

swapped = true;

}

}

}

return a;

}

const numbers = new Array(ARRAY_SIZE);

let seed = 42;

function random() {

seed = (seed * 1103515245 + 12345) & 0x7fffffff;

return seed;

}

for (let i = 0; i < ARRAY_SIZE; i++) {

numbers[i] = random();

}

const start = performance.now();

for (let iter = 0; iter < ITERATIONS; iter++) {

bubbleSort(numbers);

}

const end = performance.now();

const totalTimeMs = end - start;

const avgTimeMs = totalTimeMs / ITERATIONS;

console.log('JavaScript Benchmark Results:');

console.log(`Array size: ${ARRAY_SIZE.toLocaleString()}`);

console.log(`Iterations: ${ITERATIONS}`);

console.log(`Total time: ${totalTimeMs.toFixed(3)} ms`);

console.log(`Average time per run: ${avgTimeMs.toFixed(3)} ms`);

Run:

node bench_bubble_sort.js

Rust

// bench_bubble_sort.rs

use std::time::Instant;

const ARRAY_SIZE: usize = 1_000;

const ITERATIONS: usize = 10;

fn bubble_sort(mut a: Vec<i32>) -> Vec<i32> {

if a.is_empty() {

return a;

}

loop {

let mut swapped = false;

for i in 0..a.len().saturating_sub(1) {

if a[i] > a[i + 1] {

a.swap(i, i + 1);

swapped = true;

}

}

if !swapped {

break;

}

}

a

}

struct SimpleRng {

state: u64,

}

impl SimpleRng {

fn new(seed: u64) -> Self {

Self { state: seed }

}

fn next(&mut self) -> i32 {

self.state = self.state.wrapping_mul(1103515245).wrapping_add(12345);

(self.state >> 16) as i32

}

}

fn main() {

let mut numbers = vec![0i32; ARRAY_SIZE];

let mut rng = SimpleRng::new(42);

for i in 0..ARRAY_SIZE {

numbers[i] = rng.next();

}

let start = Instant::now();

for _iter in 0..ITERATIONS {

let copy = numbers.clone();

bubble_sort(copy);

}

let elapsed = start.elapsed();

let avg_time_ms = elapsed.as_secs_f64() * 1000.0 / ITERATIONS as f64;

println!("Rust Benchmark Results:");

println!("Array size: {}", ARRAY_SIZE);

println!("Iterations: {}", ITERATIONS);

println!("Total time: {:?}", elapsed);

println!("Average time per run: {:.3} ms", avg_time_ms);

}

Compile and run:

rustc -O bench_bubble_sort.rs -o bench_bubble_sort_rs

./bench_bubble_sort_rs

Java

// BenchBubbleSort.java

import java.util.Random;

public class BenchBubbleSort {

private static final int ARRAY_SIZE = 1_000;

private static final int ITERATIONS = 10;

public static void bubbleSort(int[] arr) {

if (arr.length == 0) return;

boolean swapped;

do {

swapped = false;

for (int i = 0; i < arr.length - 1; i++) {

if (arr[i] > arr[i + 1]) {

int temp = arr[i];

arr[i] = arr[i + 1];

arr[i + 1] = temp;

swapped = true;

}

}

} while (swapped);

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

Random rng = new Random(42);

int[] numbers = new int[ARRAY_SIZE];

for (int i = 0; i < ARRAY_SIZE; i++) {

numbers[i] = rng.nextInt();

}

// Warm up JIT

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

int[] copy = numbers.clone();

bubbleSort(copy);

}

long start = System.nanoTime();

for (int iter = 0; iter < ITERATIONS; iter++) {

int[] copy = numbers.clone();

bubbleSort(copy);

}

long end = System.nanoTime();

double totalTimeMs = (end - start) / 1_000_000.0;

double avgTimeMs = totalTimeMs / ITERATIONS;

System.out.println("Java Benchmark Results:");

System.out.println("Array size: " + ARRAY_SIZE);

System.out.println("Iterations: " + ITERATIONS);

System.out.printf("Total time: %.3f ms%n", totalTimeMs);

System.out.printf("Average time per run: %.3f ms%n", avgTimeMs);

}

}

Compile and run:

javac BenchBubbleSort.java

java BenchBubbleSort

- Test with different data patterns: random, sorted, reverse-sorted, nearly-sorted

When This Algorithm Isn't Enough

- Large datasets (n > 100): Use O(n log n) algorithms like Merge Sort, Quick Sort, or Timsort

- Real-time systems: Bubble Sort's O(n²) worst case can cause timeouts

- Memory-constrained environments: While O(1) space is good, the time cost is usually prohibitive

- Production code: Always use your language's built-in sort (typically optimized O(n log n))

Stretch goal: count comparisons and swaps

Understanding the exact cost helps you appreciate why O(n²) matters. Let's add counters to see the real work:

Python version with counters

# bubble_sort_counted.py

# Run: python3 bubble_sort_counted.py

def bubble_sort_counted(a):

"""Return (sorted_list, comparisons, swaps, passes)."""

a = list(a)

if not a:

return (a, 0, 0, 0)

comparisons = 0

swaps = 0

passes = 0

swapped = True

while swapped:

swapped = False

passes += 1

for i in range(len(a) - 1):

comparisons += 1

if a[i] > a[i + 1]:

a[i], a[i + 1] = a[i + 1], a[i]

swaps += 1

swapped = True

return (a, comparisons, swaps, passes)

if __name__ == "__main__":

data = [5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6]

sorted_data, comps, swaps, passes = bubble_sort_counted(data)

print(f"Sorted: {sorted_data}")

print(f"Comparisons: {comps}, Swaps: {swaps}, Passes: {passes}")

print(f"n={len(data)}, theoretical max comparisons: {len(data)*(len(data)-1)//2}")

What I like about this: the counting forces honesty. For n=6, the theoretical maximum is 15 comparisons, but with early exit on already-sorted data, you might only need 5. The difference between best case (O(n)) and worst case (O(n²)) becomes tangible.

Go version with the same guarantee

// bubble_sort_counted.go

// Build: go build -o bubble_sort_counted_go ./bubble_sort_counted.go

// Run: ./bubble_sort_counted_go

package main

import "fmt"

func BubbleSortCounted(a []int) (sorted []int, comparisons, swaps, passes int) {

b := append([]int(nil), a...)

if len(b) == 0 {

return b, 0, 0, 0

}

swapped := true

for swapped {

swapped = false

passes++

for i := 0; i < len(b)-1; i++ {

comparisons++

if b[i] > b[i+1] {

b[i], b[i+1] = b[i+1], b[i]

swaps++

swapped = true

}

}

}

return b, comparisons, swaps, passes

}

func main() {

data := []int{5, 2, 9, 1, 5, 6}

sorted, comps, swaps, passes := BubbleSortCounted(data)

fmt.Printf("Sorted: %v\n", sorted)

fmt.Printf("Comparisons: %d, Swaps: %d, Passes: %d\n", comps, swaps, passes)

fmt.Printf("n=%d, theoretical max comparisons: %d\n", len(data), len(data)*(len(data)-1)/2)

}

The counting makes the algorithm's behavior explicit. You can see exactly how many operations each pass requires, making the O(n²) complexity tangible.

⚠️ Common Pitfalls (and How to Avoid Them)

- Missing early exit: Forgetting the

swappedflag makes every run O(n²), even on sorted data. - Unstable variant: If you swap

≥rather than>, you break stability (equal elements may change order). - Index errors: Don't compare past

n - 2; usei < len(a) - 1ori <= len(a) - 2. - Mutation surprises: Clone input when benchmarking to avoid side effects.

- Wrong complexity expectations: Bubble Sort won't scale—and that's okay. It's a teaching tool.

- Off-by-one errors: Starting at index 0 vs 1. Always test with

[single_element]and[].

Practical safeguards that prevent problems down the road

Preconditions are not optional. Decide what "empty input" means and enforce it the same way everywhere. Return early, throw, or use an option type. Just be consistent.

State your invariant in code comments. Future you will forget. Reviewers will thank you.

Test the boring stuff. Empty list, single element, all equal, sorted ascending, sorted descending, reverse-sorted, negatives, huge values, random fuzz. Property tests make this fun instead of fragile 1.

Try It Yourself

- Count comparisons and swaps: Add counters to track the exact work done. Print totals and compare to theoretical maximums.

- Add descending order: Modify the algorithm to accept a comparator function for custom ordering.

- Animate the process: Create a visual representation using your favorite GUI framework or ASCII output showing each pass.

- Benchmark O(n²) growth visually: Plot array size vs. time to empirically confirm quadratic growth.

- Write property tests: Confirm sorted output is a permutation of input (same elements, different order).

- Optimize for nearly-sorted data: Implement Cocktail Shaker Sort (bidirectional Bubble Sort) and compare performance.

Where to Go Next

- Insertion Sort: Similar O(n²) complexity, but often faster in practice due to better cache behavior

- Selection Sort: Another simple O(n²) algorithm that guarantees O(n) swaps, making it useful when swaps are expensive

- Merge Sort: Divide-and-conquer O(n log n) algorithm that's stable and predictable

- Quick Sort: Average-case O(n log n) with O(n²) worst case, but often fastest in practice

- Timsort: Python's default sort—a hybrid algorithm that adapts to data patterns

Recommended reading:

- Introduction to Algorithms (CLRS) for deep theory on sorting

- Algorithm Visualizations for interactive sorting algorithm demos

- Practice problems on LeetCode or HackerRank

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Bubble Sort Stable?

Yes, Bubble Sort is a stable sorting algorithm. This means that elements with equal values maintain their relative order after sorting. For example, if you have [3, 1, 3, 2] and sort it, the two 3s will stay in the same relative positions: [1, 2, 3, 3] (the first 3 comes before the second 3, just like in the original).

This stability comes from the comparison A[i] > A[i+1]—it only swaps when elements are strictly out of order, not when they're equal. If you change it to A[i] >= A[i+1], you break stability.

When Would You Actually Use Bubble Sort?

Almost never in production. The only legitimate use cases are:

- Educational purposes: Teaching sorting concepts and invariants

- Tiny datasets: When n < 10, the overhead of faster algorithms isn't worth it

- Nearly-sorted data: With early exit, already-sorted arrays finish in O(n)

- Embedded systems: When memory is extremely constrained (O(1) space)

- Code reviews: Demonstrating algorithm correctness and stability

For everything else, use your language's built-in sort (typically optimized O(n log n)).

How Does Bubble Sort Compare to Other O(n²) Algorithms?

Bubble Sort is generally the slowest of the simple O(n²) algorithms:

- Insertion Sort: Often faster due to better cache behavior, especially on nearly-sorted data

- Selection Sort: Similar performance, but doesn't adapt to sorted data (always O(n²))

- Bubble Sort: The slowest, but the most visible and easiest to understand

The main advantage Bubble Sort has is its visibility—you can watch it work, which makes it excellent for teaching.

Can Bubble Sort Be Optimized?

Yes, but not enough to make it competitive:

- Early exit: Stops when no swaps occur (already covered)—this is the most important optimization

- Cocktail Shaker Sort: Bidirectional Bubble Sort, slightly faster but still O(n²)

- Comb Sort: Uses gaps larger than 1, but still O(n²) worst case

None of these optimizations change the fundamental O(n²) complexity, which is why Bubble Sort remains a teaching tool, not a production algorithm.

Wrapping Up

Bubble Sort is where computer-science students first feel time complexity in their bones—like the first time you realize your O(n²) loop just became a production incident. It's slow, simple, and unforgettable. It embodies the three pillars of algorithmic thinking: correctness, efficiency, and invariants.

Mastering it isn't about memorizing the loop—it's about seeing why the loop ends. Once you can reason about that, you can reason about anything from Merge Sort to MapReduce. The bubble sort algorithm teaches you to recognize quadratic complexity when you see it, and that recognition is worth more than any production implementation.

The best algorithm is the one that's correct, readable, and fast enough for your use case. Sometimes that's Array.sort(). Sometimes it's a hand-rolled loop for teaching. Sometimes it's understanding why O(n²) matters before you hit production. The skill is knowing which one to reach for.

Key Takeaways

- Bubble Sort = compare-and-swap until stable: Simple logic, visible process

- Best case O(n) (with early exit on sorted data); worst case O(n²) (reverse-sorted)

- In-place, stable, and predictable: O(1) space, preserves equal element order

- Excellent for teaching: Invariants, performance measurement, and algorithm correctness

- Terrible for large datasets: O(n²) complexity makes it impractical for production—and that's its point

References

[1] Cormen, Leiserson, Rivest, Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, 4th ed., MIT Press, 2022

[2] Knuth, Donald E. The Art of Computer Programming, Vol. 3: Sorting and Searching, 2nd ed., Addison-Wesley, 1998

[3] Sedgewick, Wayne. Algorithms, 4th ed., Addison-Wesley, 2011

[4] Wikipedia — "Bubble Sort." Overview of algorithm, complexity, and variants

[5] USF Computer Science Visualization Lab — Animated Sorting Algorithms

[6] MIT OpenCourseWare. "6.006 Introduction to Algorithms, Fall 2011."

[7] NIST. "Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures — Bubble Sort."

About Joshua Morris

Joshua is a software engineer focused on building practical systems and explaining complex ideas clearly.