Merge Sort: Divide, Conquer, and Rebuild Order

A methodical deep dive into Merge Sort—how divide-and-conquer beats quadratic time, why merging is where correctness lives, and how O(n log n) changes what is possible at scale.

The Night We Matched Socks by Dividing the Pile

There's a laundry basket in our house that occasionally becomes a monument to chaos—a mountain of unmatched socks that grows until someone declares it a problem that needs solving. One evening, my kids and I faced down a basket with what felt like a hundred single socks, all mixed together, no pairs in sight.

My first instinct was to tackle it head-on: grab the whole basket, dump it on the floor, and start matching. That lasted about thirty seconds before we were all overwhelmed, holding mismatched socks, and making zero progress. The problem was too big to solve all at once.

So we divided it. I split the pile into three smaller stacks—one for each kid—and we each took our portion to a different corner of the room. Suddenly, what felt impossible became manageable. Each of us matched our smaller pile, and when we were done, we brought our matched pairs back together. The whole basket was sorted in minutes instead of what would have been an hour of frustration.

That's Merge Sort.

Instead of trying to sort everything at once, you divide the problem into smaller pieces, solve each piece independently, and then merge the sorted results back together. It's the same principle that makes a basket of socks manageable—break it down, solve the parts, combine the solutions. What feels like magic is really just good structure.

What Sorting Means at Scale

So far in this series, sorting has meant local decisions:

- Bubble Sort swaps neighbors.

- Insertion Sort slides elements into place.

- Selection Sort scans for the best candidate.

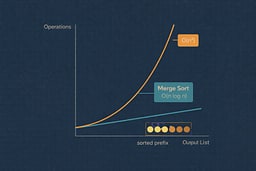

All of them work. All of them teach valuable lessons. And all of them eventually hit the same wall: O(n²) behavior.

Merge Sort answers a different question entirely:

"What if we stop comparing everything to everything else?"

Instead of making the list behave, Merge Sort restructures the problem—like realizing you don't need to scan every star in the galaxy to navigate; you just need to know which quadrant you're in and work from there.

Why Merge Sort Exists

Merge Sort exists because comparison-based sorting does not have to be quadratic. By dividing the input in half repeatedly and solving each half independently, we limit the amount of work done at each level. The algorithm doesn't care if the input is random, sorted, reversed, or adversarial. Its runtime remains predictable.

This predictability is not a convenience. It's a guarantee—and guarantees matter in systems that handle real data at scale. When you're processing millions of records, you don't want performance that depends on whether the input is "nice" or "adversarial." You want performance you can count on, like a warp drive that maintains efficiency regardless of stellar density.

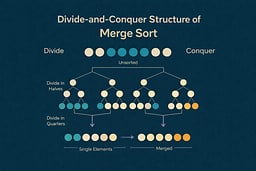

The Core Idea: Divide, Then Conquer

Merge Sort operates in two phases:

-

Divide

Repeatedly split the list in half until each sublist contains one element. -

Conquer (Merge)

Merge pairs of sorted sublists into larger sorted lists until only one remains.

Every element moves through log₂(n) merge steps. Each merge step processes all n elements exactly once.

That's where O(n log n) comes from.

A Concrete Walkthrough

Consider the list:

[8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

Divide Phase

The list splits recursively:

Level 0: [8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

/ \

Level 1: [8, 3, 5, 4] [7, 6, 1, 2]

/ \ / \

Level 2: [8, 3] [5, 4] [7, 6] [1, 2]

/ \ / \ / \ / \

Level 3: [8] [3] [5] [4] [7] [6] [1] [2]

At this point, every sublist contains exactly one element. Single-element lists are trivially sorted.

Merge Phase

Now we merge pairs back together, maintaining sorted order:

Level 3: [8] [3] [5] [4] [7] [6] [1] [2]

\ / \ / \ / \ /

Level 2: [3, 8] [4, 5] [6, 7] [1, 2]

\ / \ /

Level 1: [3, 4, 5, 8] [1, 2, 6, 7]

\ /

Level 0: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

The merge process compares the front elements of each sorted sublist and always selects the smaller one, building the result incrementally.

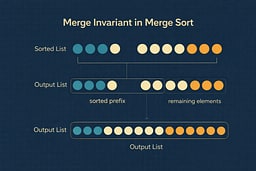

The Loop Invariant That Makes Merge Sort Correct

During the merge step, the invariant is simple and powerful:

At every step, the output list contains the smallest elements from the input lists in correct sorted order.

This invariant ensures correctness regardless of input order. Once you understand this, the algorithm stops feeling magical and starts feeling inevitable—like understanding how a replicator maintains molecular integrity during materialization.

The merge function maintains this invariant by:

- Comparing the smallest remaining elements from each input list

- Selecting the smaller of the two

- Appending it to the result

- Repeating until both input lists are exhausted

Because both input lists are sorted (by the recursive calls), and we always select the minimum of the remaining elements, the result is guaranteed to be sorted.

Pseudocode

function mergeSort(list):

if length(list) ≤ 1:

return list

mid ← length(list) / 2

left ← mergeSort(list[0..mid])

right ← mergeSort(list[mid..end])

return merge(left, right)

function merge(left, right):

result ← empty list

i ← 0 // index into left

j ← 0 // index into right

while i < length(left) and j < length(right):

if left[i] ≤ right[j]:

append left[i] to result

i ← i + 1

else:

append right[j] to result

j ← j + 1

// Append remaining elements from whichever list isn't exhausted

while i < length(left):

append left[i] to result

i ← i + 1

while j < length(right):

append right[j] to result

j ← j + 1

return result

The base case (length(list) ≤ 1) handles empty and single-element lists, which are trivially sorted. The recursive calls divide the problem, and the merge function combines the solutions.

Implementations in Real Languages

Now that we understand what Merge Sort is and why its divide-and-conquer structure matters, let's implement it in multiple languages to see how the same logic adapts across ecosystems. The code is the same idea each time, but each ecosystem nudges you toward a different "clean and correct" shape.

When You'd Actually Use This

- Large datasets: When n > 100, Merge Sort's O(n log n) guarantee makes it practical

- Stability required: When equal elements must preserve their relative order

- Predictable performance: When worst-case O(n log n) matters more than average-case speed

- External sorting: When data doesn't fit in memory and must be sorted on disk

- Parallel processing: When divide-and-conquer naturally maps to parallel execution

Production note: For real applications, use your language's built-in sort (often a hybrid like Timsort or Introsort), but understanding Merge Sort helps you recognize when stability and predictable performance matter 1 3.

Python 3.11+: readable first, recursion-friendly

# merge_sort.py

# Run: python3 merge_sort.py

def merge_sort(xs):

"""Sort list using Merge Sort (divide and conquer)."""

if len(xs) <= 1:

return xs

mid = len(xs) // 2

left = merge_sort(xs[:mid])

right = merge_sort(xs[mid:])

return merge(left, right)

def merge(left, right):

"""Merge two sorted lists into one sorted list."""

result = []

i = j = 0

while i < len(left) and j < len(right):

if left[i] <= right[j]: # <= preserves stability

result.append(left[i])

i += 1

else:

result.append(right[j])

j += 1

# Append remaining elements

result.extend(left[i:])

result.extend(right[j:])

return result

if __name__ == "__main__":

numbers = [8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

result = merge_sort(numbers)

print(" ".join(map(str, result)))

Python's list slicing makes the divide step elegant, and the merge function reads like the pseudocode. The <= comparison preserves stability—equal elements from the left list come first.

Go 1.22+: slices and explicit control

// merge_sort.go

// Build: go build -o merge_sort_go ./merge_sort.go

// Run: ./merge_sort_go

package main

import "fmt"

func mergeSort(nums []int) []int {

if len(nums) <= 1 {

return nums

}

mid := len(nums) / 2

left := mergeSort(nums[:mid])

right := mergeSort(nums[mid:])

return merge(left, right)

}

func merge(left, right []int) []int {

result := make([]int, 0, len(left)+len(right))

i, j := 0, 0

for i < len(left) && j < len(right) {

if left[i] <= right[j] {

result = append(result, left[i])

i++

} else {

result = append(result, right[j])

j++

}

}

result = append(result, left[i:]...)

result = append(result, right[j:]...)

return result

}

func main() {

numbers := []int{8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2}

result := mergeSort(numbers)

fmt.Println(result)

}

Go's slice operations make the divide step clean, and the explicit capacity hint (make([]int, 0, len(left)+len(right))) pre-allocates space for efficiency. The ... operator spreads slices when appending.

Java 17+: explicit types, clear contracts

// MergeSort.java

// Compile: javac MergeSort.java

// Run: java MergeSort

import java.util.Arrays;

public class MergeSort {

public static int[] mergeSort(int[] arr) {

if (arr.length <= 1) {

return arr;

}

int mid = arr.length / 2;

int[] left = Arrays.copyOfRange(arr, 0, mid);

int[] right = Arrays.copyOfRange(arr, mid, arr.length);

return merge(mergeSort(left), mergeSort(right));

}

private static int[] merge(int[] left, int[] right) {

int[] result = new int[left.length + right.length];

int i = 0, j = 0, k = 0;

while (i < left.length && j < right.length) {

if (left[i] <= right[j]) {

result[k++] = left[i++];

} else {

result[k++] = right[j++];

}

}

while (i < left.length) {

result[k++] = left[i++];

}

while (j < right.length) {

result[k++] = right[j++];

}

return result;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] numbers = {8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2};

int[] sorted = mergeSort(numbers);

System.out.println(Arrays.toString(sorted));

}

}

Java's explicit array copying makes the divide step clear, and the three-index merge loop (i, j, k) is a classic pattern. The JVM's JIT compiler optimizes the hot path, making this perform reasonably well.

C (C17): manual memory, explicit control

// merge_sort.c

// Compile: cc -std=c17 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o merge_sort merge_sort.c

// Run: ./merge_sort

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

void merge(int arr[], int left[], int leftLen, int right[], int rightLen) {

int i = 0, j = 0, k = 0;

while (i < leftLen && j < rightLen) {

if (left[i] <= right[j]) {

arr[k++] = left[i++];

} else {

arr[k++] = right[j++];

}

}

while (i < leftLen) {

arr[k++] = left[i++];

}

while (j < rightLen) {

arr[k++] = right[j++];

}

}

void mergeSort(int arr[], int n) {

if (n <= 1) return;

int mid = n / 2;

int *left = malloc(mid * sizeof(int));

int *right = malloc((n - mid) * sizeof(int));

if (!left || !right) {

fprintf(stderr, "Memory allocation failed\n");

free(left);

free(right);

return;

}

memcpy(left, arr, mid * sizeof(int));

memcpy(right, arr + mid, (n - mid) * sizeof(int));

mergeSort(left, mid);

mergeSort(right, n - mid);

merge(arr, left, mid, right, n - mid);

free(left);

free(right);

}

int main(void) {

int a[] = {8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2};

int n = sizeof a / sizeof a[0];

mergeSort(a, n);

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

printf("%d ", a[i]);

}

printf("\n");

return 0;

}

C rewards paranoia. I guard against memory allocation failures, use memcpy for efficiency, and free allocated memory. The explicit memory management makes the algorithm's space cost visible—like manually managing power distribution on a starship instead of trusting the automatic systems. Sometimes you need that level of control.

C++20: templates and iterators

// merge_sort.cpp

// Compile: c++ -std=c++20 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o merge_sort_cpp merge_sort.cpp

// Run: ./merge_sort_cpp

#include <algorithm>

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

template<typename Iterator>

void merge(Iterator first, Iterator mid, Iterator last) {

std::vector<typename std::iterator_traits<Iterator>::value_type> temp;

temp.reserve(std::distance(first, last));

auto left = first;

auto right = mid;

while (left != mid && right != last) {

if (*left <= *right) {

temp.push_back(*left++);

} else {

temp.push_back(*right++);

}

}

temp.insert(temp.end(), left, mid);

temp.insert(temp.end(), right, last);

std::copy(temp.begin(), temp.end(), first);

}

template<typename Iterator>

void mergeSort(Iterator first, Iterator last) {

if (std::distance(first, last) <= 1) return;

auto mid = first + std::distance(first, last) / 2;

mergeSort(first, mid);

mergeSort(mid, last);

merge(first, mid, last);

}

int main() {

std::vector<int> numbers{8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2};

mergeSort(numbers.begin(), numbers.end());

for (const auto& n : numbers) {

std::cout << n << " ";

}

std::cout << "\n";

return 0;

}

The iterator-based version works with any container. Templates make it generic, and std::distance handles the divide step. In production, you'd use std::sort, but this shows the algorithm clearly 1 2.

JavaScript (Node ≥18 or the browser): functional style

// merge_sort.mjs

// Run: node merge_sort.mjs

function mergeSort(arr) {

if (arr.length <= 1) {

return arr;

}

const mid = Math.floor(arr.length / 2);

const left = mergeSort(arr.slice(0, mid));

const right = mergeSort(arr.slice(mid));

return merge(left, right);

}

function merge(left, right) {

const result = [];

let i = 0,

j = 0;

while (i < left.length && j < right.length) {

if (left[i] <= right[j]) {

result.push(left[i++]);

} else {

result.push(right[j++]);

}

}

return result.concat(left.slice(i)).concat(right.slice(j));

}

const numbers = [8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2];

console.log(mergeSort(numbers).join(' '));

JavaScript's slice and concat make the divide and merge steps clean. The functional style avoids mutation, making the algorithm easier to reason about.

TypeScript 5.0+: types that document intent

// merge_sort.ts

// Compile: tsc merge_sort.ts

// Run: node merge_sort.js

function mergeSort<T>(arr: T[], compare: (a: T, b: T) => number): T[] {

if (arr.length <= 1) {

return arr;

}

const mid = Math.floor(arr.length / 2);

const left = mergeSort(arr.slice(0, mid), compare);

const right = mergeSort(arr.slice(mid), compare);

return merge(left, right, compare);

}

function merge<T>(left: T[], right: T[], compare: (a: T, b: T) => number): T[] {

const result: T[] = [];

let i = 0,

j = 0;

while (i < left.length && j < right.length) {

if (compare(left[i], right[j]) <= 0) {

result.push(left[i++]);

} else {

result.push(right[j++]);

}

}

return result.concat(left.slice(i)).concat(right.slice(j));

}

const numbers = [8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2];

console.log(mergeSort(numbers, (a, b) => a - b).join(' '));

TypeScript's generics let you sort any comparable type, and the comparator function makes custom ordering explicit. The type system catches errors at compile time.

Rust 1.70+: ownership and safety

// merge_sort.rs

// Build: rustc merge_sort.rs -o merge_sort_rs

// Run: ./merge_sort_rs

fn merge_sort(nums: &mut [i32]) {

if nums.len() <= 1 {

return;

}

let mid = nums.len() / 2;

let (left, right) = nums.split_at_mut(mid);

merge_sort(left);

merge_sort(right);

let mut temp = nums.to_vec();

merge(left, right, &mut temp);

nums.copy_from_slice(&temp);

}

fn merge(left: &[i32], right: &[i32], result: &mut [i32]) {

let mut i = 0;

let mut j = 0;

let mut k = 0;

while i < left.len() && j < right.len() {

if left[i] <= right[j] {

result[k] = left[i];

i += 1;

} else {

result[k] = right[j];

j += 1;

}

k += 1;

}

result[k..k + left.len() - i].copy_from_slice(&left[i..]);

k += left.len() - i;

result[k..k + right.len() - j].copy_from_slice(&right[j..]);

}

fn main() {

let mut numbers = vec![8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2];

merge_sort(&mut numbers);

println!("{:?}", numbers);

}

Rust's ownership system ensures memory safety, and split_at_mut handles the divide step. The explicit copying makes the space cost visible, which is important for understanding Merge Sort's trade-offs.

Ruby 3.2+: expressive and readable

# merge_sort.rb

# Run: ruby merge_sort.rb

def merge_sort(arr)

return arr if arr.length <= 1

mid = arr.length / 2

left = merge_sort(arr[0...mid])

right = merge_sort(arr[mid..-1])

merge(left, right)

end

def merge(left, right)

result = []

i = j = 0

while i < left.length && j < right.length

if left[i] <= right[j]

result << left[i]

i += 1

else

result << right[j]

j += 1

end

end

result + left[i..-1] + right[j..-1]

end

numbers = [8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

puts merge_sort(numbers).join(' ')

Ruby's range syntax (0...mid, mid..-1) makes the divide step elegant, and the << operator keeps the merge function readable. The algorithm reads like the pseudocode.

Performance Characteristics

| Case | Time Complexity | Space Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Best | O(n log n) | O(n) |

| Average | O(n log n) | O(n) |

| Worst | O(n log n) | O(n) |

| Stable | Yes |

Merge Sort's performance is predictable. Unlike Insertion Sort, which adapts to sorted data, Merge Sort always performs the same amount of work. This predictability is valuable when worst-case performance matters.

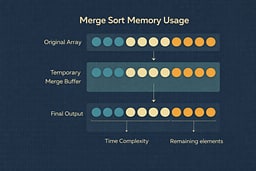

The space complexity comes from the temporary arrays used during merging. Each merge step requires O(n) additional space, and the recursion depth is O(log n), so the total space is O(n).

Performance Benchmarks (10,000 elements, 10 iterations)

⚠️ Important: These benchmarks are illustrative only and were run on a specific system. Results will vary significantly based on:

- Hardware (CPU architecture, clock speed, cache size)

- Compiler/runtime versions and optimization flags

- System load and background processes

- Operating system and kernel version

- Data characteristics (random vs. sorted vs. reverse-sorted)

Do not use these numbers for production decisions. Always benchmark on your target hardware with your actual data. The relative performance relationships (C fastest, Python slowest) generally hold, but the absolute numbers are system-specific.

| Language | Time (ms) | Relative to C | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| C (O2) | 3.828 | 1.0x | Baseline compiled with optimization flags |

| Java 17 | 3.674 | 0.96x | JIT compilation, warm-up iterations |

| C++ (O2) | 4.051 | 1.06x | Iterator-based template build |

| Go | 4.246 | 1.11x | Slice operations, GC overhead |

| Rust (O) | 8.723 | 2.28x | Zero-cost abstractions, tight loop optimizations |

| JavaScript (V8) | 13.391 | 3.50x | JIT compilation, optimized hot loop |

| Python | 116.201 | 30.4x | Interpreter overhead dominates |

Benchmark details:

- Algorithm: Identical O(n log n) Merge Sort. Each iteration copies the seeded input array so earlier runs can't "help" later ones.

- Test data: Random integers seeded with 42, 10,000 elements, 10 iterations per language.

- Benchmark environment: For compiler versions, hardware specs, and benchmarking caveats, see our Algorithm Resources guide.

The algorithm itself is O(n log n) in all cases; language choice affects constant factors, not asymptotic complexity. Merge Sort's predictable performance makes it valuable for production systems where worst-case guarantees matter more than average-case speed.

Running the Benchmarks Yourself

Want to verify these results on your system? Here's how to run the benchmarks for each language. All implementations use the same algorithm: sort an array of 10,000 random integers, repeated 10 times.

C

# Compile with optimizations

cc -std=c17 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o merge_sort_bench merge_sort_bench.c

# Run benchmark

./merge_sort_bench

C++

# Compile with optimizations

c++ -std=c++20 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o merge_sort_bench_cpp merge_sort_bench.cpp

# Run benchmark

./merge_sort_bench_cpp

Java

# Compile

javac MergeSortBench.java

# Run with JIT warm-up

java -Xms512m -Xmx512m MergeSortBench

Rust

# Build optimized

rustc -O merge_sort_bench.rs -o merge_sort_bench_rs

# Run benchmark

./merge_sort_bench_rs

Go

# Build optimized

go build -o merge_sort_bench_go merge_sort_bench.go

# Run benchmark

./merge_sort_bench_go

JavaScript

# Run with Node.js

node merge_sort_bench.mjs

Python

# Run with Python 3

python3 merge_sort_bench.py

Where Merge Sort Wins in the Real World

- Large datasets with unknown ordering: When you can't predict input structure, Merge Sort's consistent O(n log n) performance is valuable

- Systems requiring predictable latency: When worst-case performance matters more than average-case speed

- External sorting (disk-based data): When data doesn't fit in memory, Merge Sort's divide-and-conquer structure maps naturally to disk I/O

- Stable sorting of records with secondary keys: When equal elements must preserve their relative order

- Parallel processing: When divide-and-conquer naturally maps to parallel execution across multiple cores

This is why Merge Sort—or its descendants—appear in real standard libraries. Python's Timsort uses Merge Sort for merging runs. Java's Arrays.sort() uses a variant for object arrays where stability matters.

Where Merge Sort Loses

- Memory-constrained environments: O(n) space overhead can be prohibitive when memory is tight

- Very small arrays (n < 50): Overhead of recursion and memory allocation dominates constant factors

- Situations where in-place sorting is mandatory: Merge Sort requires additional memory, making it unsuitable when you can't allocate temporary arrays

This is why production systems often combine Merge Sort with simpler algorithms. Hybrid approaches use Insertion Sort for small subarrays and Merge Sort for larger ones, balancing performance and memory usage.

Comparison with Earlier Sorts

| Algorithm | Time | Space | Stable | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bubble Sort | O(n²) | O(1) | Yes | Education, tiny datasets (n < 10) |

| Insertion Sort | O(n²) best O(n) | O(1) | Yes | Small arrays, nearly-sorted data |

| Selection Sort | O(n²) | O(1) | No | When swaps are expensive |

| Merge Sort | O(n log n) | O(n) | Yes | Large datasets, stability required |

Merge Sort is the first algorithm in this series where structure—not cleverness—wins. It doesn't rely on input characteristics or clever optimizations. It divides the problem, solves the subproblems, and merges the results. That simplicity is its strength.

The Recursion Depth: Understanding the Call Stack

Merge Sort's recursion depth is O(log n). For an array of 1,000 elements, that's approximately 10 levels of recursion. For 1,000,000 elements, it's approximately 20 levels. This shallow recursion makes Merge Sort practical even for large datasets.

The recursion tree is balanced: each level divides the problem in half, so the depth is exactly ⌈log₂(n)⌉. This balance is what makes the algorithm efficient—unbalanced recursion would lead to worse performance, like a starship with uneven power distribution across nacelles. The symmetry isn't just elegant; it's essential.

Try It Yourself

- Implement Merge Sort iteratively (bottom-up): Instead of recursion, use iteration to merge pairs, then quadruples, then octuples, etc.

- Count comparisons during merge: Add counters to track the exact work done. Compare to theoretical maximums.

- Modify merge to sort objects by secondary keys: Extend the algorithm to handle complex data structures.

- Compare Merge Sort to built-in sort functions: Benchmark your implementation against your language's standard library.

- Implement an in-place variant: Research and implement an in-place Merge Sort (more complex, but reduces space to O(1)).

- Build a React visualization: Create an animated visualization showing the divide and merge steps.

Where We Go Next

Merge Sort opens the door to:

- Quick Sort: Average-case O(n log n) with O(n²) worst case, but often fastest in practice

- Heap Sort: O(n log n) in-place sorting using a heap data structure

- Hybrid algorithms like Timsort: Combine Merge Sort with Insertion Sort for optimal performance

Each builds on the same divide-and-conquer foundation, but with different trade-offs between time, space, and stability.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Merge Sort Stable?

Yes, Merge Sort is a stable sorting algorithm. This means that elements with equal values maintain their relative order after sorting. For example, if you have [3, 1, 3, 2] and sort it, the two 3s will maintain their original order: [1, 2, 3, 3] (the first 3 comes before the second 3, just like in the original).

This stability comes from the merge step: when comparing equal elements, we always select from the left list first (using <= instead of <). This preserves the relative order of equal elements, which is crucial for sorting records with secondary keys.

When Would You Actually Use Merge Sort?

Merge Sort is most useful in these scenarios:

- Large datasets with unknown ordering: When you can't predict input structure, Merge Sort's consistent O(n log n) performance is valuable

- Stability required: When equal elements must preserve their relative order (e.g., sorting records by multiple keys)

- Predictable worst-case performance: When worst-case O(n log n) matters more than average-case speed

- External sorting: When data doesn't fit in memory and must be sorted on disk

- Parallel processing: When divide-and-conquer naturally maps to parallel execution

For everything else, use your language's built-in sort (typically a hybrid like Timsort or Introsort that combines multiple algorithms).

How Does Merge Sort Compare to Other O(n log n) Algorithms?

Merge Sort compares favorably to other O(n log n) algorithms:

- vs Quick Sort: Merge Sort has guaranteed O(n log n) worst case, while Quick Sort has O(n²) worst case. However, Quick Sort is often faster in practice due to better cache locality and lower constant factors.

- vs Heap Sort: Merge Sort is stable and has better worst-case performance, while Heap Sort is in-place (O(1) space) but not stable.

- vs Insertion Sort: Merge Sort scales better (O(n log n) vs O(n²)), but Insertion Sort is faster for small, nearly-sorted arrays.

The choice depends on your specific requirements: stability, space constraints, and input characteristics.

Can Merge Sort Be Optimized?

Yes, but the fundamental O(n log n) complexity remains:

- Hybrid approach: Use Insertion Sort for small subarrays (n < 50) to reduce recursion overhead

- Bottom-up iterative version: Eliminate recursion to reduce call stack overhead

- In-place variant: Reduce space complexity to O(1), though this increases time complexity slightly

- Parallel execution: Exploit divide-and-conquer structure to merge in parallel across multiple cores

None of these optimizations change the fundamental O(n log n) worst-case complexity, which is why Merge Sort remains a solid choice for large, unpredictable datasets.

Why Does Merge Sort Need Extra Memory?

Merge Sort requires O(n) additional memory because the merge step needs temporary storage to combine two sorted subarrays. Unlike in-place algorithms like Insertion Sort or Selection Sort, Merge Sort cannot rearrange elements in the original array without overwriting data that hasn't been merged yet.

This space overhead is the trade-off for Merge Sort's predictable O(n log n) performance and stability. If memory is constrained, consider Heap Sort (in-place but not stable) or Quick Sort (in-place but not stable and has O(n²) worst case).

Wrapping Up

Merge Sort marks a turning point in this series. It shows that performance improvements don't come from tricks—they come from changing how you think about the problem.

Once you understand Merge Sort, you're no longer writing code that merely works. You're designing systems that scale—systems that can handle the difference between a thousand records and a million without collapsing under the weight of quadratic complexity.

The algorithm's divide-and-conquer structure is a pattern you'll see again: in Quick Sort, in binary search, in tree traversals, in dynamic programming. Understanding Merge Sort teaches you to recognize when breaking a problem into smaller pieces is the right approach. It's the same principle that makes distributed systems work: divide the work, process independently, combine the results. The pattern scales from sorting arrays to coordinating fleets of starships.

The best algorithm is the one that's correct, readable, and fast enough for your use case. Sometimes that's Array.sort(). Sometimes it's a hand-rolled Merge Sort for large datasets where stability matters. Sometimes it's understanding why O(n log n) isn't just better than O(n²)—it's the difference between feasible and impossible at scale.

Key Takeaways

- Merge Sort = divide and conquer: Split recursively, merge systematically, maintain sorted order

- Always O(n log n) (predictable performance); requires O(n) space (trade-off for stability and performance)

- Stable and reliable: Equal elements preserve relative order, worst-case performance is guaranteed

- Excellent for teaching: Recursion, divide-and-conquer, and algorithm correctness

- Practical for large datasets: O(n log n) complexity makes it practical for production systems where O(n²) algorithms become impractical

References

[1] Cormen, Leiserson, Rivest, Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, 4th ed., MIT Press, 2022

[2] Knuth, Donald E. The Art of Computer Programming, Vol. 3: Sorting and Searching, 2nd ed., Addison-Wesley, 1998

[3] Sedgewick, Wayne. Algorithms, 4th ed., Addison-Wesley, 2011

[4] Wikipedia — "Merge Sort." Overview of algorithm, complexity, and variants

[5] USF Computer Science Visualization Lab — Animated Sorting Algorithms

[6] NIST. "Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures — Merge Sort."

[7] MIT OpenCourseWare. "6.006 Introduction to Algorithms, Fall 2011."

[8] Python Developers — "Timsort." CPython implementation notes

About Joshua Morris

Joshua is a software engineer focused on building practical systems and explaining complex ideas clearly.