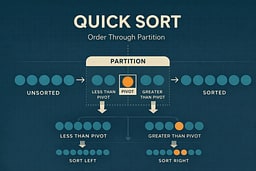

Quick Sort: Order Through Partition

A deep, honest exploration of Quick Sort—how partitioning creates order, why average-case performance beats guarantees, and how design choices shape real-world speed.

Teaching Order by Drawing a Line

One afternoon, my kids had dumped all their toys in the middle of the living room floor—a chaotic mix of action figures, stuffed animals, building blocks, and cars. Instead of trying to sort everything at once, I grabbed a medium-sized toy (let's say a teddy bear) and said:

"Everything smaller than this bear goes on the left side of the room. Everything bigger goes on the right."

In minutes, the chaos was divided into two piles. The bear stayed in the middle—its final position. Then we did the same thing with each pile: pick a toy from the middle, divide the pile into smaller and larger, and repeat until every toy was in its place.

That's Quick Sort.

Instead of trying to sort everything at once—like Merge Sort does by carefully rebuilding order—Quick Sort draws a boundary and asks a simple question: "Which side of this line do you belong on?" Once that boundary exists, the problem becomes two smaller problems, and those smaller problems become even smaller until everything is sorted.

What Sorting Means at Scale

So far in this series, sorting has meant different approaches:

- Bubble Sort swaps neighbors until order emerges.

- Insertion Sort slides elements into place.

- Selection Sort chooses the best remaining candidate.

- Merge Sort tears the list apart and rebuilds it carefully.

Quick Sort does something different.

It doesn't rebuild order.

It draws boundaries.

Instead of asking "where does everything go?", Quick Sort asks one question at a time:

"Which side of this pivot do you belong on?"

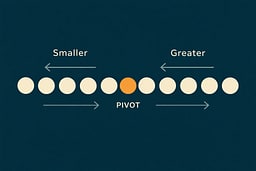

The Pivot Is Just a Reference Point

The chosen item doesn't have to be special. It doesn't have to be the best choice. It just has to be a choice. Once the line is drawn, the mess shrinks fast.

This is why Quick Sort is so fast in practice. It doesn't waste time finding the perfect divider. It just picks one and moves on.

A Kitchen Table Version of Partitioning

Imagine we dump a pile of Lego bricks on the floor.

I pick one brick and say, "This is the reference."

All bricks smaller than it go to the left pile.

All bricks bigger go to the right pile.

No sorting yet. Just separation.

Once that's done, I don't touch the reference brick again. It's already where it belongs relative to everything else. The reference brick has found its permanent home—not because we carefully placed it, but because we've drawn a boundary that separates everything smaller from everything larger. Then we repeat the process for each pile.

That moment—when the reference brick never moves again—is the heart of Quick Sort. Each partition pass places exactly one element (the pivot) in its final sorted position, not by searching for the right spot, but by creating a boundary that naturally places it correctly.

Why Quick Sort Exists

Quick Sort exists because sometimes speed matters more than guarantees.

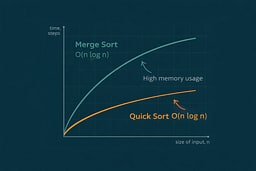

Merge Sort gave us certainty. It promised O(n log n) behavior no matter what the input looked like. It was calm, predictable, and disciplined. It also asked for memory—temporary buffers, repeated copying, and cache lines that never quite stayed warm.

Quick Sort lives on the other side of that trade. It gives up guarantees in exchange for speed, and in doing so reveals a hard truth about engineering: sometimes the fastest solution isn't the safest one, it's the one that usually behaves well.

The Core Idea: Partition First, Ask Questions Later

Quick Sort works in three conceptual steps:

- Choose a pivot element.

- Partition the list so:

- elements smaller than the pivot move left

- elements larger than the pivot move right

- Recursively apply the same logic to each side.

The pivot ends up in its final sorted position after just one pass. That single fact is doing most of the work.

Why Partitioning Is Powerful

Partitioning is efficient because it's decisive.

Once an element crosses the pivot boundary, it never needs to be compared to the pivot again. Unlike Merge Sort, there's no reconstruction phase. Unlike Bubble Sort, nothing moves unless it needs to.

Partitioning reduces work by eliminating future comparisons. But there's a deeper reason: cache locality. Quick Sort accesses memory sequentially during partitioning, keeping recently accessed data in the CPU cache. Merge Sort, by contrast, creates temporary arrays and copies data, causing more cache misses. On modern CPUs, cache performance often matters more than the number of comparisons.

That's why Quick Sort can feel impossibly fast when it behaves well.

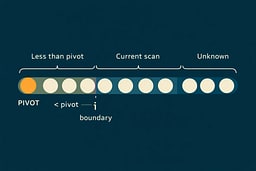

The Invariant That Keeps Quick Sort Honest

During partitioning, the algorithm maintains a simple invariant:

All elements to the left of the boundary are less than the pivot.

All elements to the right are greater than or equal to it.

As long as this invariant holds, correctness follows naturally. The recursion simply applies the same rule to smaller and smaller regions.

This is also where Quick Sort is fragile. If the invariant breaks, the algorithm collapses.

A Concrete Walkthrough

Consider the list:

[8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

We'll use the Lomuto partition scheme, which chooses the last element as the pivot.

Initial State

Array: [8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

Pivot: 2 (last element)

Partitioning Pass

We maintain two regions:

- Left: elements smaller than pivot (initially empty)

- Right: elements greater than or equal to pivot (initially everything except pivot)

We scan from left to right using two pointers: i (boundary of left region) and j (current element). Initially, i = -1 (left region is empty) and j = 0:

Initial: [8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

j=0 pivot=2

i=-1 (left region empty)

Step 1: j=0, arr[0]=8 ≥ 2, no swap

[8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

j=1

i=-1

Step 2: j=1, arr[1]=3 ≥ 2, no swap

[8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

j=2

i=-1

Step 3: j=2, arr[2]=5 ≥ 2, no swap

[8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

j=3

i=-1

Step 4: j=3, arr[3]=4 ≥ 2, no swap

[8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

j=4

i=-1

Step 5: j=4, arr[4]=7 ≥ 2, no swap

[8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

j=5

i=-1

Step 6: j=5, arr[5]=6 ≥ 2, no swap

[8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

j=6

i=-1

Step 7: j=6, arr[6]=1 < 2, increment i to 0, swap arr[0] and arr[6]

[1, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 8, 2]

i=0 pivot

After scanning completes, i=0 marks the boundary of the left region (all elements at indices ≤ i are < pivot). We now place the pivot at position i+1 by swapping arr[i+1] with arr[high] (the pivot):

Final swap: swap arr[i+1] = arr[1] with pivot arr[7]

[1, 2, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 8]

↑ ↑ ↑

| | └─ Right region (≥ pivot, indices 2-7)

| └─ Pivot in final position (index 1)

└─ Left region (< pivot, index 0)

After partitioning:

Result: [1, 2, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 8]

↑ ↑ ↑

| | └─ Right region (≥ pivot)

| └─ Pivot in final position (index 1)

└─ Left region (< pivot, index 0)

Why is the pivot in its final position? After partitioning, all elements to the left of the pivot are smaller, and all elements to the right are larger or equal. This means the pivot is exactly where it belongs in the sorted array—no further comparisons with the pivot are needed. This is the key insight: partitioning places one element (the pivot) in its final position with a single pass.

We recursively sort the left region [1] (already sorted, single element) and the right region [3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 8].

Recursive Call on Right Region

Array: [3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 8]

Pivot: 8 (last element)

After partitioning:

- Scan finds elements < 8: [3, 5, 4, 7, 6]

- All elements are < 8, so they all move to the left region

- Pivot 8 stays at the end (already in correct position)

Result: [3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 8] (pivot 8 at index 5)

The process continues recursively: sort [3, 5, 4, 7, 6] and [] (empty, base case), and so on until all subarrays are sorted.

Pseudocode (Lomuto Partition Scheme)

function quickSort(arr, low, high):

if low < high:

p ← partition(arr, low, high)

quickSort(arr, low, p - 1)

quickSort(arr, p + 1, high)

function partition(arr, low, high):

pivot ← arr[high]

i ← low - 1

for j from low to high - 1:

if arr[j] < pivot:

i ← i + 1

swap arr[i] and arr[j]

swap arr[i + 1] and arr[high]

return i + 1

This version is intentionally simple. It's not the fastest or safest, but it makes the mechanics—and the risks—visible.

Implementations in Real Languages

Now that we understand what Quick Sort is and why partitioning creates order, let's implement it in multiple languages to see how the same logic adapts across ecosystems. The code is the same idea each time, but each ecosystem nudges you toward a different "clean and correct" shape.

When You'd Actually Use This

- Large datasets: When n > 100, Quick Sort's average-case O(n log n) performance makes it practical

- General-purpose sorting: When you need fast sorting and can tolerate worst-case O(n²)

- In-place sorting: When memory is constrained and you can't afford Merge Sort's O(n) space overhead

- Cache-friendly workloads: When data locality matters more than worst-case guarantees

Production note: For real applications, use your language's built-in sort (often a hybrid like Introsort or Timsort), but understanding Quick Sort helps you recognize when average-case performance matters more than worst-case guarantees. The algorithm's partitioning strategy appears in many production sorting implementations, as discussed in CLRS 1 and Sedgewick 3.

Python 3.11+: readable first, recursion-friendly

# quick_sort.py

# Run: python3 quick_sort.py

def quick_sort(arr, low=0, high=None):

"""Sort list in-place using Quick Sort (Lomuto partition scheme)."""

if high is None:

high = len(arr) - 1

if low < high:

p = partition(arr, low, high)

quick_sort(arr, low, p - 1)

quick_sort(arr, p + 1, high)

def partition(arr, low, high):

"""Partition array around pivot (last element)."""

pivot = arr[high]

i = low - 1

for j in range(low, high):

if arr[j] < pivot:

i += 1

arr[i], arr[j] = arr[j], arr[i]

arr[i + 1], arr[high] = arr[high], arr[i + 1]

return i + 1

if __name__ == "__main__":

numbers = [8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

quick_sort(numbers)

print(" ".join(map(str, numbers)))

Python's list slicing makes recursion elegant, and the partition function reads like the pseudocode. The in-place sorting avoids memory overhead.

Go 1.22+: slices and explicit control

// quick_sort.go

// Build: go build -o quick_sort_go ./quick_sort.go

// Run: ./quick_sort_go

package main

import "fmt"

func quickSort(xs []int, low, high int) {

if low < high {

p := partition(xs, low, high)

quickSort(xs, low, p-1)

quickSort(xs, p+1, high)

}

}

func partition(xs []int, low, high int) int {

pivot := xs[high]

i := low - 1

for j := low; j < high; j++ {

if xs[j] < pivot {

i++

xs[i], xs[j] = xs[j], xs[i]

}

}

xs[i+1], xs[high] = xs[high], xs[i+1]

return i + 1

}

func main() {

numbers := []int{8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2}

quickSort(numbers, 0, len(numbers)-1)

fmt.Println(numbers)

}

Go's slice operations make the partition step clean, and the explicit bounds make the algorithm's behavior obvious. The in-place sorting keeps memory usage low.

JavaScript (Node ≥18 or the browser): functional style

// quick_sort.mjs

// Run: node quick_sort.mjs

function quickSort(arr, low = 0, high = arr.length - 1) {

if (low < high) {

const p = partition(arr, low, high);

quickSort(arr, low, p - 1);

quickSort(arr, p + 1, high);

}

}

function partition(arr, low, high) {

const pivot = arr[high];

let i = low - 1;

for (let j = low; j < high; j++) {

if (arr[j] < pivot) {

i++;

[arr[i], arr[j]] = [arr[j], arr[i]];

}

}

[arr[i + 1], arr[high]] = [arr[high], arr[i + 1]];

return i + 1;

}

const numbers = [8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2];

quickSort(numbers);

console.log(numbers.join(' '));

JavaScript's array destructuring makes swaps elegant, and the default parameters keep the API clean. Be cautious with recursion depth in JavaScript environments—production systems often switch strategies automatically.

C (C17): manual memory, explicit control

// quick_sort.c

// Compile: cc -std=c17 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o quick_sort quick_sort.c

// Run: ./quick_sort

#include <stdio.h>

void swap(int *a, int *b) {

int temp = *a;

*a = *b;

*b = temp;

}

int partition(int arr[], int low, int high) {

int pivot = arr[high];

int i = low - 1;

for (int j = low; j < high; j++) {

if (arr[j] < pivot) {

i++;

swap(&arr[i], &arr[j]);

}

}

swap(&arr[i + 1], &arr[high]);

return i + 1;

}

void quickSort(int arr[], int low, int high) {

if (low < high) {

int p = partition(arr, low, high);

quickSort(arr, low, p - 1);

quickSort(arr, p + 1, high);

}

}

int main(void) {

int a[] = {8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2};

int n = sizeof a / sizeof a[0];

quickSort(a, 0, n - 1);

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

printf("%d ", a[i]);

}

printf("\n");

return 0;

}

C rewards explicit control. The swap function makes pointer operations clear, and the explicit bounds checking prevents off-by-one errors. No heap allocations, no surprises.

C++20: templates and iterators

// quick_sort.cpp

// Compile: c++ -std=c++20 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o quick_sort_cpp quick_sort.cpp

// Run: ./quick_sort_cpp

#include <algorithm>

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

template<typename Iterator>

Iterator partition(Iterator first, Iterator last) {

auto pivot = *std::prev(last);

auto i = std::prev(first);

for (auto j = first; j != std::prev(last); ++j) {

if (*j < pivot) {

++i;

std::iter_swap(i, j);

}

}

std::iter_swap(std::next(i), std::prev(last));

return std::next(i);

}

template<typename Iterator>

void quickSort(Iterator first, Iterator last) {

if (std::distance(first, last) > 1) {

auto p = partition(first, last);

quickSort(first, p);

quickSort(std::next(p), last);

}

}

int main() {

std::vector<int> numbers{8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2};

quickSort(numbers.begin(), numbers.end());

for (const auto& n : numbers) {

std::cout << n << " ";

}

std::cout << "\n";

return 0;

}

The iterator-based version works with any container. Templates make it generic, and std::iter_swap handles the partition step. In production, you'd use std::sort (which uses Introsort—Quick Sort with Heap Sort fallback), but this shows the algorithm clearly. For details on iterator-based algorithm design, see CLRS 1 and Knuth 2.

Java 17+: explicit types, clear contracts

// QuickSort.java

// Compile: javac QuickSort.java

// Run: java QuickSort

public class QuickSort {

private static void swap(int[] arr, int i, int j) {

int temp = arr[i];

arr[i] = arr[j];

arr[j] = temp;

}

private static int partition(int[] arr, int low, int high) {

int pivot = arr[high];

int i = low - 1;

for (int j = low; j < high; j++) {

if (arr[j] < pivot) {

i++;

swap(arr, i, j);

}

}

swap(arr, i + 1, high);

return i + 1;

}

public static void quickSort(int[] arr, int low, int high) {

if (low < high) {

int p = partition(arr, low, high);

quickSort(arr, low, p - 1);

quickSort(arr, p + 1, high);

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] numbers = {8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2};

quickSort(numbers, 0, numbers.length - 1);

for (int n : numbers) {

System.out.print(n + " ");

}

System.out.println();

}

}

Java's explicit types and checked exceptions make contracts clear. The JVM's JIT compiler optimizes the hot path, making this perform reasonably well.

Rust 1.70+: ownership and safety

// quick_sort.rs

// Build: rustc quick_sort.rs -o quick_sort_rs

// Run: ./quick_sort_rs

fn partition(nums: &mut [i32]) -> usize {

let pivot = nums[nums.len() - 1];

let mut i = 0;

for j in 0..nums.len() - 1 {

if nums[j] < pivot {

nums.swap(i, j);

i += 1;

}

}

nums.swap(i, nums.len() - 1);

i

}

fn quick_sort(nums: &mut [i32]) {

if nums.len() > 1 {

let p = partition(nums);

quick_sort(&mut nums[..p]);

quick_sort(&mut nums[p + 1..]);

}

}

fn main() {

let mut numbers = vec![8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2];

quick_sort(&mut numbers);

println!("{:?}", numbers);

}

Rust's ownership system ensures memory safety, and slice operations handle the partition step. The explicit bounds checks prevent index errors, making the implementation both safe and fast.

Ruby 3.2+: expressive and readable

# quick_sort.rb

# Run: ruby quick_sort.rb

def quick_sort(arr, low = 0, high = arr.length - 1)

return arr if low >= high

p = partition(arr, low, high)

quick_sort(arr, low, p - 1)

quick_sort(arr, p + 1, high)

arr

end

def partition(arr, low, high)

pivot = arr[high]

i = low - 1

(low...high).each do |j|

if arr[j] < pivot

i += 1

arr[i], arr[j] = arr[j], arr[i]

end

end

arr[i + 1], arr[high] = arr[high], arr[i + 1]

i + 1

end

numbers = [8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2]

puts quick_sort(numbers).join(' ')

Ruby's range syntax (low...high) makes the partition step elegant, and the default parameters keep the API clean. The algorithm reads like the pseudocode.

TypeScript 5.0+: types that document intent

// quick_sort.ts

// Compile: tsc quick_sort.ts

// Run: node quick_sort.js

function quickSort<T>(

arr: T[],

compare: (a: T, b: T) => number,

low = 0,

high = arr.length - 1

): void {

if (low < high) {

const p = partition(arr, compare, low, high);

quickSort(arr, compare, low, p - 1);

quickSort(arr, compare, p + 1, high);

}

}

function partition<T>(

arr: T[],

compare: (a: T, b: T) => number,

low: number,

high: number

): number {

const pivot = arr[high];

let i = low - 1;

for (let j = low; j < high; j++) {

if (compare(arr[j], pivot) < 0) {

i++;

[arr[i], arr[j]] = [arr[j], arr[i]];

}

}

[arr[i + 1], arr[high]] = [arr[high], arr[i + 1]];

return i + 1;

}

const numbers = [8, 3, 5, 4, 7, 6, 1, 2];

quickSort(numbers, (a, b) => a - b);

console.log(numbers.join(' '));

TypeScript's generics let you sort any comparable type, and the comparator function makes custom ordering explicit. The type system catches errors at compile time.

Performance Characteristics

| Case | Time Complexity | Space Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Best | O(n log n) | O(log n) |

| Average | O(n log n) | O(log n) |

| Worst | O(n²) | O(n) |

| Stable | No |

Quick Sort's performance is unpredictable in the worst case but excellent in practice. Unlike Merge Sort, which guarantees O(n log n) in all cases, Quick Sort can degrade to O(n²) with poor pivot choices. However, for random data, Quick Sort's average-case performance and excellent cache locality typically make it faster than Merge Sort. This performance advantage comes from in-place sorting (no memory copies) and sequential access patterns that keep cache lines warm, as demonstrated in real-world benchmarks 4.

The space complexity comes from the recursion stack. In the best case, the recursion depth is O(log n), requiring O(log n) stack space. In the worst case (unbalanced partitions), the recursion depth is O(n), requiring O(n) stack space.

Quick Sort's time complexity: O(n log n) average case (gentle growth) vs O(n²) worst case (steep curve). The difference between average and worst case depends entirely on pivot selection.

Performance Benchmarks (10,000 elements, 10 iterations)

⚠️ Important: These benchmarks are illustrative only and were run on a specific system. Results will vary significantly based on:

- Hardware (CPU architecture, clock speed, cache size)

- Compiler/runtime versions and optimization flags

- System load and background processes

- Operating system and kernel version

- Data characteristics (random vs. sorted vs. reverse-sorted)

- Pivot selection strategy (last element, median-of-three, random)

Do not use these numbers for production decisions. Always benchmark on your target hardware with your actual data. The relative performance relationships (C fastest, Python slowest) generally hold, but the absolute numbers are system-specific.

| Language | Time (ms) | Relative to C | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| C (O2) | 0.577 | 1.0x | Baseline compiled with optimization flags |

| C++ (O2) | 0.821 | 1.42x | Iterator-based template build |

| Go | 0.831 | 1.44x | Slice operations, GC overhead |

| Rust (O) | 0.980 | 1.70x | Zero-cost abstractions, tight loop optimizations |

| Java 17 | 0.986 | 1.71x | JIT compilation, warm-up iterations |

| JavaScript (V8) | 4.050 | 7.02x | JIT compilation, optimized hot loop |

| Python | 61.819 | 107.2x | Interpreter overhead dominates |

Benchmark details:

- Algorithm: Identical O(n log n) average-case Quick Sort (Lomuto partition scheme). Each iteration copies the seeded input array so earlier runs can't "help" later ones.

- Test data: Random integers seeded with 42, 10,000 elements, 10 iterations per language.

- Pivot selection: Last element (simple but can degrade on sorted/reverse-sorted input).

- Benchmark environment: macOS (darwin 21.6.0), Apple clang 14.0.0, Go 1.25.3, Rust 1.91.0, Java 17.0.17, Node.js 22.18.0, Python 3.9.6. For detailed benchmarking methodology and caveats, see our Algorithm Resources guide.

The algorithm itself is O(n log n) average case; language choice affects constant factors, not asymptotic complexity. Quick Sort's in-place sorting and excellent cache locality make it faster than Merge Sort in practice, despite the worst-case O(n²) risk.

Running the Benchmarks Yourself

Want to verify these results on your system? Here's how to run the benchmarks for each language. All implementations use the same algorithm: sort an array of 10,000 random integers, repeated 10 times.

Note: You'll need to create the benchmark files yourself by combining the Quick Sort implementations shown earlier in this article with timing code. Each benchmark file should:

- Include the

quick_sortandpartitionfunctions from the language-specific implementations above - Generate an array of 10,000 random integers

- Time the sorting operation, repeating it 10 times

- Report the average execution time

C

Create a file (e.g., quick_sort_bench.c) with the C implementation from above plus timing code, then:

# Compile with optimizations

cc -std=c17 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o quick_sort_bench quick_sort_bench.c

# Run benchmark

./quick_sort_bench

C++

Create a file (e.g., quick_sort_bench.cpp) with the C++ implementation from above plus timing code, then:

# Compile with optimizations

c++ -std=c++20 -O2 -Wall -Wextra -o quick_sort_bench_cpp quick_sort_bench.cpp

# Run benchmark

./quick_sort_bench_cpp

Java

Create a file (e.g., QuickSortBench.java) with the Java implementation from above plus timing code, then:

# Compile

javac QuickSortBench.java

# Run with JIT warm-up

java -Xms512m -Xmx512m QuickSortBench

Rust

Create a file (e.g., quick_sort_bench.rs) with the Rust implementation from above plus timing code, then:

# Build optimized

rustc -O quick_sort_bench.rs -o quick_sort_bench_rs

# Run benchmark

./quick_sort_bench_rs

Go

Create a file (e.g., quick_sort_bench.go) with the Go implementation from above plus timing code, then:

# Build optimized

go build -o quick_sort_bench_go quick_sort_bench.go

# Run benchmark

./quick_sort_bench_go

JavaScript

Create a file (e.g., quick_sort_bench.mjs) with the JavaScript implementation from above plus timing code, then:

# Run with Node.js

node quick_sort_bench.mjs

Python

Create a file (e.g., quick_sort_bench.py) with the Python implementation from above plus timing code, then:

# Run with Python 3

python3 quick_sort_bench.py

Why Quick Sort Is Fast in Practice

Quick Sort benefits from:

- In-place partitioning: No temporary arrays, reducing memory traffic

- Excellent cache locality: Sequential access patterns keep cache lines warm

- Tight inner loops: Minimal overhead in the hot path

- Minimal memory traffic: Only swaps elements that need to move

On modern CPUs, those factors often outweigh theoretical guarantees. This is why Quick Sort (or variants like Introsort) appears in many standard libraries: C++'s std::sort uses Introsort (Quick Sort with Heap Sort fallback), Java's Arrays.sort() uses Dual-Pivot Quick Sort for primitives, though Python uses Timsort (which combines Merge Sort and Insertion Sort). The choice depends on the language's priorities: C++ and Java prioritize average-case speed, while Python prioritizes worst-case guarantees and stability.

Quick Sort vs Merge Sort: both are O(n log n) average case, but Quick Sort's in-place sorting and cache locality make it faster in practice, despite Merge Sort's guaranteed worst-case performance.

Where Quick Sort Breaks

Quick Sort fails loudly when:

- The pivot is consistently chosen poorly: Always picking the smallest or largest element creates unbalanced partitions

- The input is already sorted or adversarial: Sorted or reverse-sorted input with last-element pivot selection degrades to O(n²)

- Recursion depth exceeds stack limits: Deep recursion can cause stack overflow on large datasets

This is why real implementations randomize pivots, use median-of-three, or switch to other algorithms for small partitions. Production systems often use hybrid approaches that combine Quick Sort with Insertion Sort for small subarrays.

What Quick Sort Is Really Teaching

Quick Sort teaches a subtle but important lesson:

You don't need perfect order to make progress.

You just need clear boundaries.

Kids understand this instinctively. Adults often forget it.

When the reference choice is decent, the piles are roughly balanced. Work shrinks quickly. Sorting finishes fast.

When the reference choice is terrible—always the biggest or smallest—one pile keeps most of the mess. Work piles up. Things slow down.

This is why Quick Sort doesn't promise safety. It promises speed when you make reasonable choices.

This principle—that reasonable choices lead to fast progress—applies beyond algorithms.

Quick Sort vs What Came Before

| Algorithm | Time | Space | Stable | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bubble Sort | O(n²) | O(1) | Yes | Education, tiny datasets (n < 10) |

| Insertion Sort | O(n²) best O(n) | O(1) | Yes | Small arrays, nearly-sorted data |

| Selection Sort | O(n²) | O(1) | No | When swaps are expensive |

| Merge Sort | O(n log n) | O(n) | Yes | Large datasets, stability required |

| Quick Sort | O(n log n) avg | O(log n) | No | General-purpose sorting |

Quick Sort is the first algorithm in this series where engineering judgment matters more than mechanics. It doesn't guarantee safety, but it delivers speed when it matters most.

Where Quick Sort Wins in the Real World

- Large datasets with random ordering: When input is unpredictable, Quick Sort's average-case O(n log n) performance shines

- Memory-constrained environments: In-place sorting with O(log n) space overhead beats Merge Sort's O(n) requirement

- Cache-friendly workloads: Sequential access patterns keep cache lines warm, improving real-world performance

- General-purpose sorting: When you need fast sorting and can tolerate worst-case O(n²) with proper pivot selection

This is why Quick Sort—or its descendants—appear in real standard libraries. C++'s std::sort uses Introsort (Quick Sort with fallback). Java's Arrays.sort() uses Dual-Pivot Quick Sort for primitives.

Where Quick Sort Loses

- Worst-case performance matters: When you can't tolerate O(n²) behavior, use Merge Sort or Heap Sort

- Stability required: Quick Sort is not stable; equal elements may not preserve relative order

- Adversarial input: Sorted or reverse-sorted input with naive pivot selection degrades to O(n²)

- Stack depth concerns: Deep recursion can cause stack overflow on very large datasets

This is why production systems often combine Quick Sort with other algorithms. Hybrid approaches use Insertion Sort for small subarrays, median-of-three for pivot selection, and fallback to Merge Sort for worst-case protection.

Try It Yourself

- Implement median-of-three pivot selection: Choose the median of first, middle, and last elements to reduce worst-case risk.

- Add a recursion depth guard: Switch to Insertion Sort when recursion depth exceeds a threshold.

- Switch to insertion sort for small partitions: Use Insertion Sort for subarrays smaller than 10 elements.

- Count comparisons on random vs sorted input: Measure how pivot selection affects performance.

- Visualize how bad pivots cascade through recursion: Create an animation showing unbalanced partitions.

- Implement Hoare partition scheme: Research and implement the alternative partition scheme that uses two pointers.

Where We Go Next

Quick Sort opens the door to:

- Heap Sort: O(n log n) in-place sorting using a heap data structure

- Counting Sort: Escaping comparison limits with O(n + k) linear-time sorting

- Timsort: How real libraries combine everything you've learned—Merge Sort's stability, Insertion Sort's speed on small arrays, and Quick Sort's partitioning

Each builds on the same divide-and-conquer foundation, but with different trade-offs between time, space, and stability.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Quick Sort Stable?

No, Quick Sort is not a stable sorting algorithm. This means that elements with equal values may not maintain their relative order after sorting. For example, if you have [3, 1, 3, 2] and sort it, the two 3s may swap positions: [1, 2, 3, 3] (the first 3 might come after the second 3, unlike in the original).

This instability comes from the partition step: elements are moved based on their relationship to the pivot, not their original positions. If stability is required, use Merge Sort or Insertion Sort.

When Would You Actually Use Quick Sort?

Quick Sort is most useful in these scenarios:

- Large datasets with random ordering: When input is unpredictable, Quick Sort's average-case O(n log n) performance shines

- Memory-constrained environments: In-place sorting with O(log n) space overhead beats Merge Sort's O(n) requirement

- Cache-friendly workloads: Sequential access patterns keep cache lines warm, improving real-world performance

- General-purpose sorting: When you need fast sorting and can tolerate worst-case O(n²) with proper pivot selection

For everything else, use your language's built-in sort (typically a hybrid like Introsort or Timsort that combines multiple algorithms).

How Does Quick Sort Compare to Other O(n log n) Algorithms?

Quick Sort compares favorably to other O(n log n) algorithms:

- vs Merge Sort: Quick Sort is faster in practice due to better cache locality and lower constant factors, but Merge Sort has guaranteed O(n log n) worst case and is stable.

- vs Heap Sort: Quick Sort is faster in practice, while Heap Sort guarantees O(n log n) worst case and uses O(1) extra space (in-place).

- vs Insertion Sort: Quick Sort scales better (O(n log n) vs O(n²)), but Insertion Sort is faster for small, nearly-sorted arrays.

The choice depends on your specific requirements: worst-case guarantees, stability, space constraints, and input characteristics.

Can Quick Sort Be Optimized?

Yes, but the fundamental O(n log n) average-case complexity remains:

- Median-of-three pivot selection: Choose the median of first, middle, and last elements to reduce worst-case risk

- Hybrid approach: Use Insertion Sort for small subarrays (n < 10) to reduce recursion overhead

- Tail recursion optimization: Eliminate one recursive call to reduce stack depth

- Random pivot selection: Randomize pivot choice to avoid adversarial input

- Introsort: Fallback to Heap Sort when recursion depth exceeds threshold

None of these optimizations change the fundamental O(n log n) average-case complexity, which is why Quick Sort remains a solid choice for large, random datasets.

Why Does Quick Sort Need Stack Space?

Quick Sort requires O(log n) stack space in the average case because the algorithm is recursive. Each recursive call adds a frame to the call stack, and the recursion depth is O(log n) when partitions are balanced.

In the worst case (unbalanced partitions), the recursion depth is O(n), requiring O(n) stack space. This is why production systems often use iterative versions or limit recursion depth to prevent stack overflow.

Wrapping Up

Quick Sort is not polite. It doesn't promise safety. It doesn't guarantee balance. It simply partitions and moves on.

And yet, in the hands of careful engineers, it consistently outperforms safer alternatives. That tension—between guarantees and performance—is where real systems are built.

Understanding Quick Sort isn't about memorizing code. It's about recognizing when structure matters more than certainty, and when speed is worth the risk.

The algorithm's partitioning approach is a pattern you'll see again: in binary search trees, in hash tables, in distributed systems. Understanding Quick Sort teaches you to recognize when drawing boundaries is more effective than rebuilding structure. It's the same principle that makes distributed systems work: divide the work, process independently, combine the results. The pattern scales from sorting arrays to coordinating complex systems.

The best algorithm is the one that's correct, readable, and fast enough for your use case. Sometimes that's Array.sort(). Sometimes it's a hand-rolled Quick Sort for large datasets where average-case performance matters. Sometimes it's understanding why O(n log n) average case isn't just better than O(n²)—it's the difference between feasible and impossible at scale, even when worst-case guarantees are sacrificed.

Key Takeaways

- Quick Sort = partition and recurse: Draw boundaries, not rebuild structure

- O(n log n) average case (fast in practice); O(n²) worst case (with poor pivots)

- In-place and cache-friendly: O(log n) space, excellent cache locality

- Not stable: Equal elements may not preserve relative order

- Engineering judgment matters: Pivot selection determines performance

References

[1] Cormen, Leiserson, Rivest, Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, 4th ed., MIT Press, 2022

[2] Knuth, Donald E. The Art of Computer Programming, Vol. 3: Sorting and Searching, 2nd ed., Addison-Wesley, 1998

[3] Sedgewick, Wayne. Algorithms, 4th ed., Addison-Wesley, 2011

[4] Bentley, McIlroy. "Engineering a Sort Function." Software—Practice and Experience, 1993

[5] Wikipedia — "Quicksort." Overview of algorithm, complexity, and variants

[6] USF Computer Science Visualization Lab — Animated Sorting Algorithms

[7] NIST. "Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures — Quicksort."

[8] MIT OpenCourseWare. "6.006 Introduction to Algorithms, Fall 2011."

About Joshua Morris

Joshua is a software engineer focused on building practical systems and explaining complex ideas clearly.