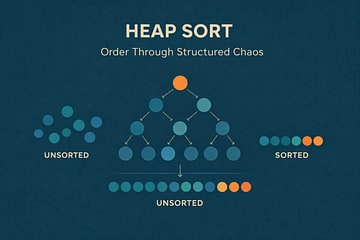

Heap Sort: Order Through Structured Chaos

A practical deep dive into Heap Sort—how binary heaps work, why heap sort guarantees O(n log n), and how it compares to quicksort, mergesort, and selection sort across real systems.

One evening, my kids were building a complicated LEGO set and hit the same problem every builder does: finding the right pieces quickly. We didn’t try to sort everything perfectly. Instead, we made a big “most likely” pile, kept the largest pieces easy to grab, and reshuffled whenever the pile got messy. The goal wasn’t perfection—it was keeping the next needed piece close at hand.

That is a heap.

Heap Sort doesn’t try to fully order everything at once. It builds a structure that guarantees the most important thing is always easy to find, then removes it, fixes the structure, and repeats.

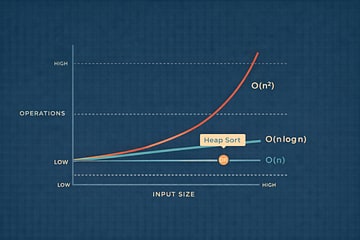

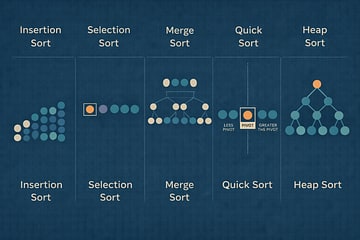

Sorting algorithms often reveal more about system design than about ordering data. Some favor simplicity, others favor speed, and a few prioritize predictability above all else. Heap Sort belongs firmly in the last category. It guarantees O(n log n) time complexity regardless of input, uses constant extra space, and avoids recursion entirely. These properties make Heap Sort less flashy than Quick Sort and less elegant than Merge Sort, but also far more dependable under adversarial conditions.1

This article examines Heap Sort as both an algorithm and a design philosophy. We will explore how heaps work, why Heap Sort behaves the way it does, and where it fits among the sorting algorithms already covered in this series. Along the way, we will implement Heap Sort in several languages, benchmark its performance, and discuss the trade-offs that make it valuable in real systems.

Heapsort at a Glance

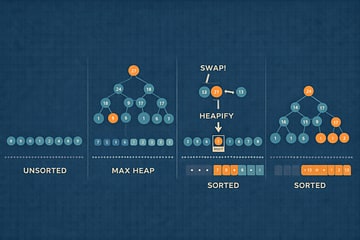

Heapsort is a comparison-based sorting algorithm that uses a binary heap to sort an array in place. It starts by building a max-heap so the largest value is always at the root, then repeatedly swaps that root with the last unsorted element and re-heapifies the remaining heap. The result is a fully sorted array with a dependable O(n log n) time bound in all cases.4 5

Think of it as two tight phases:

- Build the heap: Rearrange the array into a max-heap so parent nodes are always ≥ their children.4

- Extract and restore: Swap the root to the end, shrink the heap by one, and heapify down to restore the max-heap property.4 5

Time is O(n log n) regardless of input (meaning as the list gets bigger, the work grows roughly like “n times the number of times you can halve n,” so doubling the list size increases work a bit more than double, and it won’t suddenly get way worse on already-sorted data), space is O(1) auxiliary (meaning it uses only a tiny, fixed amount of extra memory beyond the array itself—no big helper arrays), and the algorithm is not stable (meaning if two items compare equal, they might swap positions, so their original order isn’t guaranteed to be preserved).4

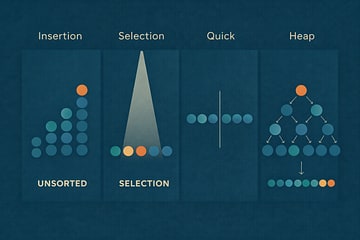

Why Heap Sort Exists

Heap Sort addresses a specific problem left open by earlier algorithms. Insertion Sort and Selection Sort are easy to reason about but scale poorly. Merge Sort offers reliable performance but requires additional memory. Quick Sort is fast in practice but vulnerable to worst-case inputs. Heap Sort exists to provide a consistent alternative: a sorting algorithm with guaranteed performance, minimal memory usage, and predictable behavior.1

This predictability matters in systems where inputs cannot be trusted. In embedded environments, real-time systems, or security-sensitive applications, worst-case guarantees are not theoretical concerns. They are operational requirements. Heap Sort sacrifices some average-case speed to ensure that no input causes catastrophic degradation, which explains why it continues to appear in standard libraries and textbooks.

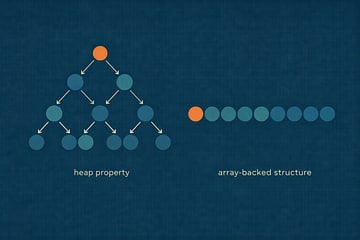

What a Heap Actually Is

A heap is not a sorted structure. It is a partially ordered structure that enforces a single invariant: in a max heap, every parent node is greater than or equal to its children; in a min heap, every parent node is less than or equal to its children. No other ordering guarantees exist. Siblings are unordered, and subtrees may contain elements far from their final sorted positions.1

This limited guarantee is intentional. By ensuring that the largest element is always accessible at the root, the heap makes selection efficient while keeping maintenance costs low. Heap Sort leverages this property repeatedly, extracting the maximum element and restoring the heap invariant until the array is sorted.

The Heap Sort Strategy

Heap Sort proceeds in two distinct phases. First, it transforms the input array into a max heap. Second, it repeatedly removes the root element and places it at the end of the array, shrinking the heap by one element each time. After each removal, the heap property is restored through a process known as heapification.1

Each extraction places one element into its final position. The algorithm does not revisit that element. As a result, the sorted portion of the array grows steadily from right to left, while the remaining elements maintain the heap structure.

Pseudocode

heapSort(array):

buildMaxHeap(array)

for i from n - 1 down to 1:

swap array[0] with array[i]

heapify(array, size = i, root = 0)

This pseudocode captures the entire algorithm. All complexity arises from maintaining the heap invariant efficiently, not from the high-level structure. The algorithm is boring on purpose. Boring is reliable.

Why Heap Sort Is O(n log n)

Building a heap from an unsorted array takes O(n) time, a result that often surprises new readers. Each extraction then requires O(log n) time to restore the heap invariant. Because the algorithm performs n extractions, the total time complexity is O(n log n).1

Unlike Quick Sort, Heap Sort does not depend on favorable input distributions. Unlike Merge Sort, it does not allocate additional arrays. These guarantees make Heap Sort a reliable baseline when performance must be bounded tightly.

Implementations

C (C17)

void heapify(int arr[], int n, int i) {

int largest = i;

int l = 2*i + 1;

int r = 2*i + 2;

if (l < n && arr[l] > arr[largest]) largest = l;

if (r < n && arr[r] > arr[largest]) largest = r;

if (largest != i) {

int tmp = arr[i];

arr[i] = arr[largest];

arr[largest] = tmp;

heapify(arr, n, largest);

}

}

void heapSort(int arr[], int n) {

for (int i = n / 2 - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

heapify(arr, n, i);

}

for (int i = n - 1; i > 0; i--) {

int tmp = arr[0];

arr[0] = arr[i];

arr[i] = tmp;

heapify(arr, i, 0);

}

}

C exposes the algorithm’s mechanics directly. Every index calculation and swap is explicit, making correctness and performance transparent.

C++20

void heapify(std::vector<int>& arr, int n, int i) {

int largest = i;

int l = 2 * i + 1;

int r = 2 * i + 2;

if (l < n && arr[l] > arr[largest]) largest = l;

if (r < n && arr[r] > arr[largest]) largest = r;

if (largest != i) {

std::swap(arr[i], arr[largest]);

heapify(arr, n, largest);

}

}

void heapSort(std::vector<int>& arr) {

int n = static_cast<int>(arr.size());

for (int i = n / 2 - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

heapify(arr, n, i);

}

for (int i = n - 1; i > 0; i--) {

std::swap(arr[0], arr[i]);

heapify(arr, i, 0);

}

}

C++ keeps the same index math while letting the container manage memory and bounds.

Python 3.11+

def heapify(arr, n, i):

largest = i

l, r = 2*i + 1, 2*i + 2

if l < n and arr[l] > arr[largest]:

largest = l

if r < n and arr[r] > arr[largest]:

largest = r

if largest != i:

arr[i], arr[largest] = arr[largest], arr[i]

heapify(arr, n, largest)

def heap_sort(arr):

n = len(arr)

for i in range(n // 2 - 1, -1, -1):

heapify(arr, n, i)

for i in range(n - 1, 0, -1):

arr[0], arr[i] = arr[i], arr[0]

heapify(arr, i, 0)

Although Python includes a heap library, implementing Heap Sort manually clarifies how the invariant is preserved.

JavaScript (Node ≥18)

function heapify(arr, n, i) {

let largest = i;

let l = 2 * i + 1;

let r = 2 * i + 2;

if (l < n && arr[l] > arr[largest]) largest = l;

if (r < n && arr[r] > arr[largest]) largest = r;

if (largest !== i) {

[arr[i], arr[largest]] = [arr[largest], arr[i]];

heapify(arr, n, largest);

}

}

function heapSort(arr) {

const n = arr.length;

for (let i = Math.floor(n / 2) - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

heapify(arr, n, i);

}

for (let i = n - 1; i > 0; i--) {

[arr[0], arr[i]] = [arr[i], arr[0]];

heapify(arr, i, 0);

}

}

JavaScript’s destructuring assignment simplifies swaps without obscuring the algorithm’s logic.

TypeScript 5.0+

function heapify(arr: number[], n: number, i: number): void {

let largest = i;

const l = 2 * i + 1;

const r = 2 * i + 2;

if (l < n && arr[l] > arr[largest]) largest = l;

if (r < n && arr[r] > arr[largest]) largest = r;

if (largest !== i) {

[arr[i], arr[largest]] = [arr[largest], arr[i]];

heapify(arr, n, largest);

}

}

function heapSort(arr: number[]): void {

const n = arr.length;

for (let i = Math.floor(n / 2) - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

heapify(arr, n, i);

}

for (let i = n - 1; i > 0; i--) {

[arr[0], arr[i]] = [arr[i], arr[0]];

heapify(arr, i, 0);

}

}

TypeScript adds contracts without changing the algorithm’s shape.

Go 1.22+

func heapify(arr []int, n, i int) {

largest := i

l, r := 2*i+1, 2*i+2

if l < n && arr[l] > arr[largest] {

largest = l

}

if r < n && arr[r] > arr[largest] {

largest = r

}

if largest != i {

arr[i], arr[largest] = arr[largest], arr[i]

heapify(arr, n, largest)

}

}

func heapSort(arr []int) {

n := len(arr)

for i := n/2 - 1; i >= 0; i-- {

heapify(arr, n, i)

}

for i := n - 1; i > 0; i-- {

arr[0], arr[i] = arr[i], arr[0]

heapify(arr, i, 0)

}

}

Go’s clarity reinforces Heap Sort’s mechanical nature. There is little room for ambiguity.

Java 17+

static void heapify(int[] arr, int n, int i) {

int largest = i;

int l = 2 * i + 1;

int r = 2 * i + 2;

if (l < n && arr[l] > arr[largest]) largest = l;

if (r < n && arr[r] > arr[largest]) largest = r;

if (largest != i) {

int tmp = arr[i];

arr[i] = arr[largest];

arr[largest] = tmp;

heapify(arr, n, largest);

}

}

static void heapSort(int[] arr) {

int n = arr.length;

for (int i = n / 2 - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

heapify(arr, n, i);

}

for (int i = n - 1; i > 0; i--) {

int tmp = arr[0];

arr[0] = arr[i];

arr[i] = tmp;

heapify(arr, i, 0);

}

}

Java keeps the algorithm explicit and predictable, with no hidden allocation.

Rust 1.70+

fn heapify(arr: &mut [i32], n: usize, i: usize) {

let mut largest = i;

let l = 2 * i + 1;

let r = 2 * i + 2;

if l < n && arr[l] > arr[largest] {

largest = l;

}

if r < n && arr[r] > arr[largest] {

largest = r;

}

if largest != i {

arr.swap(i, largest);

heapify(arr, n, largest);

}

}

fn heap_sort(arr: &mut [i32]) {

let n = arr.len();

for i in (0..n / 2).rev() {

heapify(arr, n, i);

}

for i in (1..n).rev() {

arr.swap(0, i);

heapify(arr, i, 0);

}

}

Rust’s ownership model keeps the swaps safe without changing the core logic.

Ruby 3.2+

def heapify(arr, n, i)

largest = i

l = 2 * i + 1

r = 2 * i + 2

largest = l if l < n && arr[l] > arr[largest]

largest = r if r < n && arr[r] > arr[largest]

if largest != i

arr[i], arr[largest] = arr[largest], arr[i]

heapify(arr, n, largest)

end

end

def heap_sort(arr)

n = arr.length

(n / 2 - 1).downto(0) { |i| heapify(arr, n, i) }

(n - 1).downto(1) do |i|

arr[0], arr[i] = arr[i], arr[0]

heapify(arr, i, 0)

end

end

Ruby reads like pseudocode while still reflecting the same heap mechanics.

Benchmarks

Performance Benchmarks (1,000 elements, 10 iterations)

⚠️ Important: These benchmarks are illustrative only and were run on a specific system. Results will vary significantly based on:

- Hardware (CPU architecture, clock speed, cache size)

- Compiler/runtime versions and optimization flags

- System load and background processes

- Operating system and kernel version

- Data characteristics (random vs. sorted vs. reverse-sorted)

Do not use these numbers for production decisions. Always benchmark on your target hardware with your actual data. The relative performance relationships generally hold, but the absolute numbers are system-specific.

| Language | Time (ms) | Relative to C | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| C (O2) | 0.083 | 1.00x | Baseline compiled with Apple clang |

| C++ (O2) | 0.119 | 1.44x | Vector-based implementation |

| Go | 0.082 | 0.99x | go1.25.3; slice copy per iteration |

| Rust (O) | 0.061 | 0.73x | rustc 1.91.0, optimized build |

| Java 17 | 0.333 | 4.01x | JIT overhead on small input sizes |

| JavaScript (V8) | 0.812 | 9.78x | Node.js 22.18.0 |

| TypeScript | 0.758 | 9.13x | tsc 5.9.3, run via Node.js |

| Ruby | 3.469 | 41.80x | Ruby 2.6.10 interpreter |

| Python | 7.622 | 91.83x | CPython 3.9.6 interpreter |

Benchmark details:

- Algorithm: In-place Heap Sort (max heap), identical logic across languages.

- Test data: Random integers seeded with 42, 1,000 elements, 10 iterations per language. Each iteration copies the seeded input array so earlier runs cannot influence later ones.

- Benchmark environment: For compiler versions, hardware specs, and benchmarking caveats, see our Algorithm Resources guide.

Heap Sort does not dominate average-case benchmarks. Its value lies in eliminating pathological cases.

Where Heap Sort Wins

Heap Sort excels when predictability matters more than raw speed. It is suitable for systems with tight memory constraints, environments that forbid recursion, and applications exposed to adversarial inputs. These characteristics explain its continued relevance in foundational computer science education and low-level system design.

Where Heap Sort Falls Short

Heap Sort is not stable, performs poorly with respect to cache locality, and is often slower than Quick Sort on typical data.3 4 In applications where average-case performance dominates and inputs are trusted, other algorithms are often preferable.

Conclusion

Heap Sort demonstrates that algorithm design is often about managing trade-offs rather than maximizing a single metric. By accepting modest average-case performance in exchange for strict guarantees, Heap Sort occupies a distinct and valuable place in the algorithmic toolkit.

Understanding Heap Sort deepens one’s understanding of heaps themselves, which appear throughout computer science in priority queues, schedulers, and graph algorithms. The algorithm’s relevance extends beyond sorting, making it an essential concept for any serious study of data structures.

References

[1] Cormen, Leiserson, Rivest, Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, 4th ed., MIT Press, 2022

[2] Knuth, Donald E. The Art of Computer Programming, Vol. 3: Sorting and Searching, 2nd ed., Addison-Wesley, 1998

[3] Sedgewick, Wayne. Algorithms, 4th ed., Addison-Wesley, 2011

[4] Wikipedia — "Heapsort." Overview of algorithm, complexity, and variants

[5] Codecademy — "Heapsort Explained: Algorithm, Implementation, and Complexity Analysis"

[6] USF Computer Science Visualization Lab — Animated Sorting Algorithms

[7] NIST. "Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures — Heapsort."

[8] MIT OpenCourseWare. "6.006 Introduction to Algorithms, Fall 2011."

About Joshua Morris

Joshua is a software engineer focused on building practical systems and explaining complex ideas clearly.